Niq Mhlongo is one of my favourite South African storytellers. He is the author of three novels (Dog Eat Dog, After Tears, Way Back Home) which have been reprinted several times and translated into other languages like French and Spanish. Mhlongo is also well known for his short stories. His debut collection, Affluenza, gave readers a fascinating insight into contemporary South Africa. In those stories, Mhlongo tackled such wide-ranging issues as suicide and farm murders, exposing our prejudices and inability to communicate. He writes about the crucial nexus between race, gender and class and has a wicked sense of humour, often making you laugh while you squirm with discomfort.

Niq Mhlongo is one of my favourite South African storytellers. He is the author of three novels (Dog Eat Dog, After Tears, Way Back Home) which have been reprinted several times and translated into other languages like French and Spanish. Mhlongo is also well known for his short stories. His debut collection, Affluenza, gave readers a fascinating insight into contemporary South Africa. In those stories, Mhlongo tackled such wide-ranging issues as suicide and farm murders, exposing our prejudices and inability to communicate. He writes about the crucial nexus between race, gender and class and has a wicked sense of humour, often making you laugh while you squirm with discomfort.

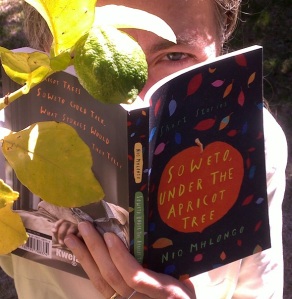

Soweto, Under the Apricot Tree is Mhlongo’s second collection of short stories which takes us on a similar journey as the one before. The topics are as diverse, but the execution even more sophisticated. Mhlongo is one of those writers who go from strength to strength with every book. “If the apricot trees of Soweto could talk, what stories would they tell?” The question on the book’s back cover invites us to ponder. Stories are the easiest way of travelling to anywhere in the world, and Soweto, Under the Apricot Tree takes us into the heart of the famous township of Johannesburg. Unfortunately, in the fourteen years I have lived in South Africa, I have not had an opportunity to visit Soweto yet apart from when experiencing it through the eyes of some of its greatest storytellers. And having read everything else Mhlongo has written, I felt I was in good hands while embarking on this particular literary trip.

The short story is considered a tough genre to write, and an even tougher one to sell. As a writer, you have to make the limited space count. Mhlongo knows exactly how to lure you in and make you want to know more. Consider these opening lines for a few of the stories: “The bizarre address you gave me some ten years ago is still stuck in my memory.” Or: “Oupa Eastwood has reported the same incident more than ten times at different police stations.” Or: “Sitting next to the coffin were five men dressed in black suits.” And then you find out that the bizarre address referred to is in a cemetery. The incident Oupa Eastwood reports is of seeing “people attempting to commit suicide at the big hole near his home in Riverlea.” And despite the sombre occasion mentioned in the last of the three quotes above, you cannot help but smile soon after when you come across the following inverted reference to a popular classic: “the Dobsonville people had to deal with the fact that the marriage and the three funerals were happening on the same day.”

Mhlongo knows how to keep his readers hooked and guessing. As to the selling of his fiction, he doesn’t only wait for the publishers and booksellers to do their job. He is known for going from place to place and offering his books to interested readers from the boot of his car. And for those lucky ones to encounter him on his path, I bet he throws in a tale or two into the bargain.

The eleven short stories in Soweto, Under the Apricot Tree are at times heart-wrenching, but the overwhelming impression they leave behind is one of satisfaction and delight in the art of the telling.

In the collection’s titular story a family gathers under an apricot tree on the day they unveil a tombstone for one of their relatives who passed away the previous year. Food is served and drink loosens some tongues. Secrets kept for many years spill out in the hours which follow.

At the centre of “My Father’s Eyes” is also a secret which leads a woman on a quest to search for her absent father: “Mokete was convinced it was my fault that our daughter was born with cerebral palsy. He insisted that I find my father and appease my ancestors with traditional sacrifices to make things right.”

In “Curiosity Killed the Cat”, two neighbouring families and cultures clash over the drowning of Bonaparte, a cat. Following the cat’s funeral, the Phalas family finds it difficult to connect to their grieving neighbours, the Moerdyks: “None of the cards came from the Phalas. They could not mourn. For them, and for Ousie Maria, a cat was just another animal. It could not be equated to a human being. In fact, to most Africans a cat is a symbol of witchcraft and bad luck.” But Ousie Maria has a different worry concerning the dead cat and as the conflict escalates, she has to face her own believes and guilt concerning the animal’s drowning.

Opinions and expectations collide on board of a flight to the UK in “Turbulence” when a young black scholar has to endure the ramblings of an elderly white lady relocating to her family in Australia: “I’m glad to see young black people like you studying”, she tells him. “You know, South Africa is going to the dogs because we’re led by uneducated people. That’s why I’m leaving.” Their journey takes an unforeseen turn which makes you look at their lives anew.

In “Nailed”, MEC Mgobhozi and one of his mistresses experience the shock of their lives when the woman’s husband comes home to find them together and decides to deal with the adulterers in his own way. Another romance ends badly in “Private Dancer Saudade”. “My heart has been broken before, but you are the first and the last person to break my life”, the narrator explains in a letter to her lover.

Like anywhere else, life under the apricot tree moves on in a dizzying speed and is often stranger than fiction. Niq Mhlongo brings the people and the places of Soweto to life. Between the funerals and the marriages, there are high hopes, devastating betrayals, and unexpected twists and turns as the streets of Soweto captivate on every page.

Soweto, Under the Apricot Tree

by Niq Mhlongo

Kwela, 2018

Review first published in the Cape Times, 15 June 2018.

We all know about them. They are often quite (in)famous. Most of us have encountered them in our personal lives or at work. Some of us are their victims. And no matter what you call them, once you have had to deal with one, you will never forget it. They go by many names: psychopaths, toxic people, malignant narcissists or master manipulators. All charm and seduction when you first meet them, whether socially or professionally, and then…! By the time they are done with you, nothing is the same any longer. To any human being with empathy, these people never make sense in the long run: their lies, manipulations, subterfuges, risk-taking, and constant deflection of blame and responsibility will have you tied up in knots. They live by different rules, and they always go for the kill. They are human parasites, unable to feel, emphasise or care for others. They are just brilliant at pretending that they can when it suits their own agendas.

We all know about them. They are often quite (in)famous. Most of us have encountered them in our personal lives or at work. Some of us are their victims. And no matter what you call them, once you have had to deal with one, you will never forget it. They go by many names: psychopaths, toxic people, malignant narcissists or master manipulators. All charm and seduction when you first meet them, whether socially or professionally, and then…! By the time they are done with you, nothing is the same any longer. To any human being with empathy, these people never make sense in the long run: their lies, manipulations, subterfuges, risk-taking, and constant deflection of blame and responsibility will have you tied up in knots. They live by different rules, and they always go for the kill. They are human parasites, unable to feel, emphasise or care for others. They are just brilliant at pretending that they can when it suits their own agendas. It is painful to think and write about Suzan Hackney’s courageous memoir, Tsk-Tsk: The story of a child at large, around Mother’s Day when many of us celebrate our fabulous mothers or are cherished as such by our kids. The relationship between a child and a mother is not always one of joy, and Hackney’s story is mostly one of unimaginable heartbreak. She was given up for adoption as a baby by her biological parents. Still in the hospital, the moment she found herself in the arms of the woman who was to become her mother, she started screaming her lungs out. The scream was a foreboding. Her memoir reads like a reckoning with that primal anguish she experienced as an infant and the torment which followed. It is also a story of survival in the face of impossible odds, and of laying ghosts to rest.

It is painful to think and write about Suzan Hackney’s courageous memoir, Tsk-Tsk: The story of a child at large, around Mother’s Day when many of us celebrate our fabulous mothers or are cherished as such by our kids. The relationship between a child and a mother is not always one of joy, and Hackney’s story is mostly one of unimaginable heartbreak. She was given up for adoption as a baby by her biological parents. Still in the hospital, the moment she found herself in the arms of the woman who was to become her mother, she started screaming her lungs out. The scream was a foreboding. Her memoir reads like a reckoning with that primal anguish she experienced as an infant and the torment which followed. It is also a story of survival in the face of impossible odds, and of laying ghosts to rest.