The internationally acclaimed, Durban-born writer, Elleke Boehmer, has a second short story collection out: To the Volcano, and Other Stories. Set mostly in the southern hemisphere and illuminated by the legendary southern light artists and tourists travel the world to experience, the twelve stories in this collection explore the tenuous and tenacious relationships people have with the South.

The internationally acclaimed, Durban-born writer, Elleke Boehmer, has a second short story collection out: To the Volcano, and Other Stories. Set mostly in the southern hemisphere and illuminated by the legendary southern light artists and tourists travel the world to experience, the twelve stories in this collection explore the tenuous and tenacious relationships people have with the South.

Boehmer is also a novelist and a literary scholar; her work across the disciplines is devoted to understanding the complexities involved. The way she presents her observations and insights in fiction is a balm for the soul. The one word that came to mind throughout the reading of To the Volcano was “gentleness”. Not necessarily when it comes to themes touched on in the stories – these are often anything but gentle (trauma, colonialism, illegal migration, ageing, loss, etc.) – but the way they are presented in exquisite, considered prose.

A little boy keeps his frail grandmother, who is suffering from dementia, grounded by constructing paper planes for her. A woman on holiday is given a bracelet that feels like a portal to a disquieting reality. Two shelf stackers in a supermarket connect on Valentine’s Day. The widow of a writer continues taking care of his legacy. During a trip to the titular volcano, the lives of a group of university lecturers and students are transformed: “You have lit a fire in my soul,” writes one of them to another, “My love is strong as death, its flashes are flashes of fire.”

Boehmer’s stories “flash fire”. They are about seeing, about interconnectedness and about the shifting of perspectives. By flipping the globe on its axis and placing the South at the centre of our attention, she allows us to look at the world from a vantage point that is unusually regarded as peripheral.

To the Volcano, and Other Stories

Elleke Boehmer

Myriad Editions, 2019

Review first published in the Cape Time on 20 February 2020.

Adamastor City is a first in all kinds of fascinating ways: for the author, Jaco Adriaanse, it is a debut novel and the first book in The Metronome Trilogy, and it is the first title for the new, independent publisher on the block, Burnt Toast Books, established this year by Robert Volker, who wants to focus on shorter forms and allow authors more freedom to experiment.

Adamastor City is a first in all kinds of fascinating ways: for the author, Jaco Adriaanse, it is a debut novel and the first book in The Metronome Trilogy, and it is the first title for the new, independent publisher on the block, Burnt Toast Books, established this year by Robert Volker, who wants to focus on shorter forms and allow authors more freedom to experiment. We have entered an era when biographers and literary scholars bemoan the fact that most of us have stopped writing letters, the ones composed with a pen on paper, folded into an envelope and posted to be received and perhaps kept under a pillow or in a jacket’s pocket because of the precious content they contain. For centuries, such letters were frequently lifelines to others and bore testimonies to our lives in ways that our modern world, despite all our inventions and our seeming connectedness, is no longer capable of reproducing.

We have entered an era when biographers and literary scholars bemoan the fact that most of us have stopped writing letters, the ones composed with a pen on paper, folded into an envelope and posted to be received and perhaps kept under a pillow or in a jacket’s pocket because of the precious content they contain. For centuries, such letters were frequently lifelines to others and bore testimonies to our lives in ways that our modern world, despite all our inventions and our seeming connectedness, is no longer capable of reproducing. Missing Person, the latest thriller from the author of The Three, Day Four and The White Road, Sarah Lotz, was my companion on a recent overseas flight and kept me so entertained that I hardly noticed the long hours flying by.

Missing Person, the latest thriller from the author of The Three, Day Four and The White Road, Sarah Lotz, was my companion on a recent overseas flight and kept me so entertained that I hardly noticed the long hours flying by. In his writing, Cynan Jones showcases the full potential of the short forms of prose – the novella and the short story. I have been a fan for years. The economy of his prose and the uncanny insight he offers into the human condition are a rare gift. Stillicide, his latest book, is a collection of short fictions which originated as a BBC Radio 4 series. The pieces are interlinked and centre around the theme of water, as the title suggests. “Stillicide” is defined as “a continual dropping of water” or “a right or duty relating to the collection of water from or onto adjacent land.”

In his writing, Cynan Jones showcases the full potential of the short forms of prose – the novella and the short story. I have been a fan for years. The economy of his prose and the uncanny insight he offers into the human condition are a rare gift. Stillicide, his latest book, is a collection of short fictions which originated as a BBC Radio 4 series. The pieces are interlinked and centre around the theme of water, as the title suggests. “Stillicide” is defined as “a continual dropping of water” or “a right or duty relating to the collection of water from or onto adjacent land.” In his novels, Richard Zimler, who is best known for The Last Kabbalist of Lisbon, has been chronicling Jewish history throughout the ages and from all corners of the world for many years. His latest offering is an unusual, deeply touching retelling of the gospel. At its centre, Zimler places Lazarus and allows him to tell the story in a long letter to his grandson: “Picture me endeavouring to tell you matters that will never be able to fit easily or comfortably on a roll of papyrus.”

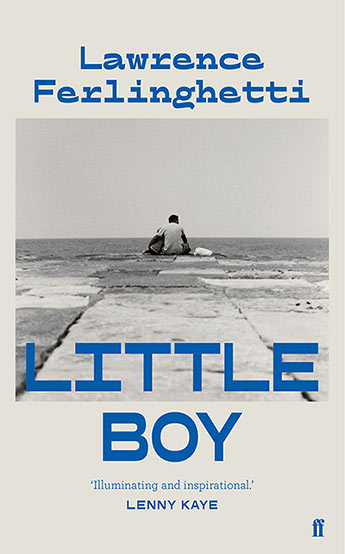

In his novels, Richard Zimler, who is best known for The Last Kabbalist of Lisbon, has been chronicling Jewish history throughout the ages and from all corners of the world for many years. His latest offering is an unusual, deeply touching retelling of the gospel. At its centre, Zimler places Lazarus and allows him to tell the story in a long letter to his grandson: “Picture me endeavouring to tell you matters that will never be able to fit easily or comfortably on a roll of papyrus.” The versatile American artist Lawrence Ferlinghetti is a literary legend. For his hundredth birthday last year, Faber & Faber published a beautiful hardback edition of his latest work, a memoir in verse titled Little Boy. The cover and the first few pages lured me in at the bookshop; I couldn’t wait to take it home.

The versatile American artist Lawrence Ferlinghetti is a literary legend. For his hundredth birthday last year, Faber & Faber published a beautiful hardback edition of his latest work, a memoir in verse titled Little Boy. The cover and the first few pages lured me in at the bookshop; I couldn’t wait to take it home. There are numerous writers out there who understand the complexity of the present. Many can also clearly convey their insights. But few do it as strikingly as Rebecca Solnit. I have discovered her work only recently, but have read and loved all the books she has authored by now. Her latest is another intellectual delight.

There are numerous writers out there who understand the complexity of the present. Many can also clearly convey their insights. But few do it as strikingly as Rebecca Solnit. I have discovered her work only recently, but have read and loved all the books she has authored by now. Her latest is another intellectual delight.

For obvious reasons, I chose to speak about a few of the women in my life who shaped my creativity and were instrumental in paving my way towards a career in writing, editing and publishing. It was impossible to honour all of them in a short time, but these are the women who featured in my talk yesterday: my grandmother, Babcia Marysia, and my Mom, both of them nurtured my creativity in indirect but significant ways; Mrs Nellie Fahy, the librarian who awakened my passion for reading; Nadine Gordimer, whose writing brought me to South Africa for the first time; Maureen Isaacson, who first gave me the opportunity to hone my craft as a book reviewer when she was book page editor of the Sunday Independent; Lyndall Gordon, whose work and friendship showed me how to continue being a writer in the world when I was doubting that I could; Rachel Zadok, who believed in me as an editor and through work kept me sane when my world lost nearly all connection to sanity; and Joanne Hichens, who was a stranger when I asked her to visit me in an hour of utter despair nearly five years ago, but we became friends and are now co-editors of an anthology of short stories we published together: HAIR: Weaving and Unpicking Stories of Identity.

For obvious reasons, I chose to speak about a few of the women in my life who shaped my creativity and were instrumental in paving my way towards a career in writing, editing and publishing. It was impossible to honour all of them in a short time, but these are the women who featured in my talk yesterday: my grandmother, Babcia Marysia, and my Mom, both of them nurtured my creativity in indirect but significant ways; Mrs Nellie Fahy, the librarian who awakened my passion for reading; Nadine Gordimer, whose writing brought me to South Africa for the first time; Maureen Isaacson, who first gave me the opportunity to hone my craft as a book reviewer when she was book page editor of the Sunday Independent; Lyndall Gordon, whose work and friendship showed me how to continue being a writer in the world when I was doubting that I could; Rachel Zadok, who believed in me as an editor and through work kept me sane when my world lost nearly all connection to sanity; and Joanne Hichens, who was a stranger when I asked her to visit me in an hour of utter despair nearly five years ago, but we became friends and are now co-editors of an anthology of short stories we published together: HAIR: Weaving and Unpicking Stories of Identity.

During the book club reviewing session, I also briefly spoke about the book I had finished reading that morning: Desiree-Anne Martin’s remarkable

During the book club reviewing session, I also briefly spoke about the book I had finished reading that morning: Desiree-Anne Martin’s remarkable  When a doctor pushed a shunt into her “unborn baby’s thorax to save his life from a deadly condition called hydrops”, Olivia Gordon and her husband had no way of knowing what other challenges would await them and their son before or after his birth.

When a doctor pushed a shunt into her “unborn baby’s thorax to save his life from a deadly condition called hydrops”, Olivia Gordon and her husband had no way of knowing what other challenges would await them and their son before or after his birth.