Braunau am Inn | Geretsdorf | Salzburg, Austria, 7 p.m.

Braunau am Inn | Geretsdorf | Salzburg, Austria, 7 p.m.

You are like me. You feel safer on the right side of the road, sitting on the left in the car, changing gears with your right hand, looking over your right shoulder to reverse. The little white Daihatsu was an unexpected gift from your father; he bought it for peanuts and renovated it so that you could have a car of your own. You should actually sell it now. Ever since your move to Cape Town, you drive it only during occasional visits to your parents, at most a few weeks every year. For the rest of the time, the reliable little car loiters in the yard gathering dust. It is much smaller and less comfortable than the respectable Mercedes you and your husband share at home, yet you feel safe in it. The idea of parting with it is painful to you, even though you know this would be the sensible thing to do. It’s what your father urges you to do every time you come to visit. He sees no point in keeping it. But no matter how hard it is to admit, even to yourself, you see it as another loss of part of your life. You have experienced too many losses; you can’t reduce it to an ordinary transaction of exchanging money for an object. This object is too special. The car and you share a history.

You have always been an intrepid traveller, and the Daihatsu has taken you to many remote corners of Europe. It has never let you down. When you were at university, you drove it to Salzburg every day, fifty kilometres each way. You would rather have it stand around and rust in the backyard of your parents’ house than sell it to a stranger. The thought of returning to it is always comforting. There was a moment when you seriously considered having it shipped to South Africa, but you soon realised that the transfer costs would have exceeded the car’s worth. It was a silly idea.

Your plane landed yesterday. You travelled from Cape Town to Munich via Amsterdam, and took the train from the airport to Simbach, Braunau’s twin, where your brother Krystian picked you up from the station. Nowadays, with the borders in the European Union abolished, the two towns are divided only by the Inn River and the usual neighbourly mistrust. For many years you lived in Braunau am Inn, Hitler’s Austrian birthplace, until your parents decided to move to the countryside and bought a house in the nearby village of Geretsdorf. Still at university, you moved with them because you had no other choice. All your life you had little say in the places you learnt to call home. Until now, that is. You moved to Cape Town because you wanted to – a traumatic liberation.

You do not visit your old house in Braunau any more. You went once and it broke your heart to see the building modernised, its small fairy garden replaced by a standard lawn, all the trees reduced to stumps. The old staghorn sumac which leant on the garage wall and in whose branches you used to read was gone. So were the deceptively straggly-looking plum trees which bore baskets of fruit every second year. Worst was the complete disappearance of the tall emerald arborvitae hedge which surrounded the entire property and gave your family privacy in the densely populated area. The place looked stripped and exposed. You felt just as violated.

You remember the time when you moved into the house after living in the States for more than two years. It was small and dilapidated, but with combined effort your family quickly turned it into a home. Here you listened to your brother dream-laugh in the bedroom next to yours; your mother filled the house with the smell of plum jam in autumn; your hard-working father fell asleep on the kitchen bench every evening after supper. This suddenly became the place where all your journeys began and ended. Even today returning to Braunau feels like a homecoming to you; it was the longest pause in your itinerant life. Nine years may not seem long, but it meant nine years of certain stability you had not experienced before.

In the early nineties, Braunau became a place of safety, in spite of its many contradictions. As an Ausländer – a foreigner – you had to stay at home when thousands of neo-Nazis descended on the town each April to celebrate the Führer’s birthday. But on other days you took your friends and visitors to the front of the house where he was born to have a look at the monument placed there. Brought over from the concentration camp in Mauthausen in 1989, the stone commemorates the victims of fascism: Für Frieden, Freiheit und Demokratie. Nie wieder Faschismus. Millionen Tote mahnen. (For peace, freedom and democracy. Never again fascism. Millions of dead warn.)

It is not a warning the generals of the former Yugoslavia took to heart when the wars broke out in 1991. You remember watching the daily media reports from the region just across the Austrian border and translating for your grandma who was staying with you at the time. The images brought back her own memories of war and displacement; it was the only time you heard her speak about that distant past. Every day she wanted to know how many more aid trucks with medicine, blankets, food and clothing had left Austria for the conflict zones. Thousands and thousands, you assured her. Somebody pointed out to you that it was not only a humanitarian gesture, but also a way of keeping the flow of refugees into Austria under some kind of control. Many came anyway. For a few months of high school you ended up sitting next to a tall, dark-haired girl whose face you still see but whose name escapes you. She told you in broken English that she didn’t know where her father and brothers were, whether they were still alive. She’d escaped only with her mother. You did not dare imagine the horrors she must have seen, the courage it must have taken to flee, what and whom they’d had to leave behind. Your own refugee past – escaping communist Poland in the late 1980s, going through refugee camps, and migrating through the world for four years – was insignificant in comparison. Your life had never been in danger. Staying at home on Hitler’s birthday to avoid creepy looks and verbal abuse from neo-Nazis hardly seemed relevant.

Earlier today, with history on your mind, you passed the Mauthausen stone monument on your way into town. The medieval Stadtplatz, the main square, was bustling with activity. The place had first been mentioned as Prounaw in an official document from 1120. As you drove into the centre, it struck you how ancient all these buildings were in comparison to the place where you lived now. Your Victorian house or even the Castle in Cape Town seemed like toddlers when compared to these Methuselahs.

In August, the light is still bright in the evening, but you had to hurry before the last shops closed at seven. Your flat in your parents’ house in Geretsdorf had stood empty for a couple of months. All day long you swept, vacuumed and dusted; then you unpacked your heavy suitcase and rushed to town to buy a few essentials. Suddenly, German was all around you. You feared to open your mouth, afraid that nothing would come out, the language you’d been speaking most of your life somehow forgotten, engulfed by a terrified silence. In the chemist, you carried a tube of your favourite toothpaste and panty liners (you always schlep both to Cape Town because you cannot find satisfying local substitutes for them) to the counter and tried your luck: Ich möchte bitte mit der Bankomatkarte zahlen. (I want to pay with my debit card.) The words flew out of your mouth, automatically. You remembered the pin code for your Austrian debit card. The woman at the counter looked familiar. At Billa you bought some Leberkas, the traditional Austrian sausage meatloaf, and a few bottles of Uttendorfer beer from a local brewery. You would have one in a hot bath later.

Now, driving back from Braunau to Geretsdorf, you think how easy it is to return, to go unnoticed, to pass as one of the locals again. The Daihatsu slides through the Upper Austrian landscape, surreally lit by the setting sun. With your right hand you smoothly shift the gear to accelerate for a takeover manoeuvre. Just as smoothly your mind shifts into a narrative mode and you describe the surroundings to yourself in your head. The kitsch pastoral scene, suddenly outrageously beautiful in the setting sun, demands some concentration: The ink-smeared horizon, the bruised horizon, dotted with eerie clouds, punctuated by clouds, glowing orange, blushing orange, from the touch of setting sunrays … The words swirl in your mind like candy around a child’s tongue. Shocked, you spit them out as you drive on and stare at the sun setting over the barley fields, the grand square, white farmsteads, the small herd of cows, and you force yourself to describe the scene in German: Der Himmel, der Horizont, blau, die Wolken, die Sonne, orange. Individual words and their particles come to you, but they refuse to turn into smooth, peppermint-sweet images. You are startled.

***

Once you’d mastered all three, you divided your languages into favourites. Polish for speaking. German for writing. English for reading. Since your move to Cape Town you have been assimilating Afrikaans into the mix, for socialising. Driving towards Geretsdorf, you recognise that a shift has taken place. The carefully ranked categories no longer apply. English has taken over.

It shouldn’t surprise you. You lived in the States for over two years, continued learning English at school in Austria, and later you studied English literature at university for twelve years. Since 2005, you’ve been living in Cape Town where it is the lingua franca. You and your husband speak English to each other and you are at home with it; it is at home with you. English has inadvertently become the language you work in, as a critic and finally – yes, finally – as a writer. You know that this last shift is the crux (even if at this very moment you have to look up the exact meaning of ‘crux’ in a monolingual dictionary to make sure that it is actually the word you mean).

English has become the language of your creativity; your intimacy with it derives from living in South Africa. But you’ve only just realised it now, on this road from Braunau to Geretsdorf. It unsettles you, this shift of paradigms which has happened so automatically, so unconsciously, and you need time to take it in; you need to think it through. In English. You recall the Chinese-Canadian writer Ying Chen speaking in Lyon about her mother tongue and the tongue of her fiction; she compared one to an arranged marriage and the other to a love affair. You can identify with the idea of English as your lover.

You arrive in Geretsdorf enlightened, in love, park the car in front of the house, and do not lock the door. At home in Cape Town, long before you get to the garage you have to start checking whether you aren’t being followed. In Geretsdorf, there are no security bars on your parterre windows, no alarms, no terrifying daily Neighbourhood Watch reports, no stories of friends’ hijacked cars, no neighbour arriving at your gate with knife wounds in his face, no phone calls from your stepdaughter traumatised after an armed robbery, no funerals of murdered family members, no foreigners burnt alive in the streets. At least not since 1945.

You derive pleasure from the unlocked car door. You enter the house with a smile and open the terrace door wide open to celebrate this sense of freedom, and to let in some fresh air before the sun sets completely. The only reason to lock up later will be to keep the mosquitoes out of your bed tonight.

From upstairs your mother calls that dinner will be ready at eight. You have a while to relax, to settle further in to one of your many former homes where everything is still so familiar. You moved into this flat after your return from a student-exchange year in Wales, and lived here for four years before you decided to make South Africa your home. It was in this very study, on this desk in front of you, where you’d planned your first journey to Africa, on a research grant for your PhD on Nadine Gordimer’s post-apartheid work. Most of your books, travel guides and maps are still here, now filed away with the photographs and study materials you’d brought from South Africa in 2004; the defended and published thesis added to the collection in 2008. There is also the photograph of you with your future husband and other participants from the ‘South Africa in Perspective’ Symposium you helped to organise at the University in Salzburg at the end of 2004. Next to it is a postcard of the picturesque Schloss Leopoldskron, where the last event of the symposium took place and where you fell in love with the man who would become your husband, even though you did not dare admit it at the time. You and your husband have returned time and again to Salzburg, the city you both love so much, the city that brought you together, with its centuries-old architecture, dignified opulence, and mummified socio-historical structures, all glossed over with gold and red for Sound of Music fans descending in their thousands, clicking away pictures in tourist-crowded alleys, stuffing themselves with grilled chestnuts or oven-baked potatoes topped with sour-cream and chives, buying useless gifts at the rustic Christmas Market, gathering next to the cathedral around the handsome Russian balalaika player, drinking hot chocolate or iced coffee at Tomaselli, ascending in cable cars to the medieval fortress that squats on top of the miniature mountain (which sometimes reminds you of another that you can see every day from your stoep in Cape Town), attending endless music concerts, trampling on the roses in the Mirabell Garden where Copernicus sits wondering whether he is German or Polish. And yes, yes, Mozart! Mozart is everywhere, more golden and reddish than anything else in the famous city of Salzburg, reclaimed covetously by a place that never wanted him during his lifetime.

You know there is more to Salzburg; it’s hidden, quiet, small, a little grey – yours. Alone, one January evening before midnight, you walked the fog-veiled streets of the old town and decided to leave Salzburg, Geretsdorf, Austria – for good. The final link in a long chain of events which began in 1999, when Edwin Hees (now a dear friend), arrived in Salzburg to share his passion for the arts of the Beloved Country and brought your whole world to a standstill. After his lecture, you rushed into the departmental library with burning cheeks and a famished mind and tried to absorb everything possible about South Africa’s past and present. You were overwhelmed by the intensity of the historical moment only five years after the first democratic election. You were moved by the promise of a new future, by the vibrancy of the emerging post-apartheid literature. History was happening then and there, at the multilingual tip of the foreign continent; it was not something confined to outdated school books. It was a time of chaos and possibility.

Travelling to South Africa for the first time in 2004 only confirmed all you’d learnt and hoped about the country in the five years since Edwin’s first lecture; strangely, you felt instantly at home in this distant, foreign, multitudinous place. No wonder that a year later, you had come home for good. South Africa was a forge, shaping history as you watched, shaping you as you lived. You abandoned the shadow of a medieval fortress, unchanged for centuries, and exchanged the crystallised reality of Europe for the muddle of a lived present. Its complexity finally tipped you over the edge of impassivity and allowed the creative impulse that you’d been harbouring for years to emerge onto the stark white light of a published page.

Now, on this visit to your parents, you sit in your old study in Geretsdorf and stare at the books that represented South Africa before it became your home. On the desk is a little pile of presents you brought for your family, among them a collection of short stories which includes one of your own. You take up a pen and dedicate the book to your parents and your brother, relieved that the content has nothing to do with them. The story is about rape and domestic violence. As one of the lucky ones, you have never experienced anything like it in your own life, but it is part of the reality of your new home, and you constantly feel the need to confront it in your writing.

South Africa is in constant flux. Positive and negative forces of change are entangled and nothing is clear-cut or easy. You sometimes think that living compartmentalised lives is the only way to survive in this fractured place. But you still want to have coffee with your gardener on the stoep while discussing the rain clouds and the mole invasion. Surely that shouldn’t be so much to ask for? Yet you know the mere suggestion makes the poor man want to sink into the nearest mole hole. (Madam?) And no matter how hard you try to explain this to your European mother, she doesn’t understand. You foolishly thought you could apply your straightforward idealism to a country that was anything but ideal. South Africa is far from unique in this respect, but this doesn’t make anything right, just more desperate. This society’s vibrancy comes at a high price. You aren’t going to change the world. The world is changing you. To try to understand, you write.

You live in a country at war with itself. It’s not paranoia, or some obscure statistics; it’s reality. Daily, thousands of people are dying around you, of preventable diseases, preventable crime, preventable poverty and, most recently, preventable xenophobia. You realise that this time the keyword of hate speech had been makwerekwere. What if the next time it is whites; will you burn to ashes in the streets with bystanders watching you helplessly or, worse, with joy? But you need not even think that far. Every day, other words are pronounced with hatred around you: baby, woman, HIV positive, privilege. There is always somebody too vulnerable for their own good. And the disquiet, the omnipotent force of history – ironically – is gathering to pounce again. But you do not stand up and fight, nor do you leave for safer shores; paralysed, from a vantage point of relative safety on your private island, you watch the ongoing catastrophes around you as if in slow motion, hoping it won’t happen to you, knowing precisely that you might be next.

Waking up from nightmares, you sometimes indulge in daydreams of fleeing, and think about the old Victorian brass bed you share with your husband, with its soft, duck-down pillows (a Christmas present from your parents), fresh linen with cream-and-yellow flower patterns (a wedding gift from your Aunt Zosia), and the luxurious, snow-white duvet cover (a token of gratitude from your Italian friend Michela).

***

Selma. Her name was Selma. You remember. The tall, dark-haired girl from Yugoslavia. What a coincidence; she shares an initial with the heroine of Slavenka Drakulić’s As If I Am Not There, the 1999 novel that has been haunting you for weeks, ever since you saw the photo of the man burning in the street.

It’s a simple, cruel story: “S. is a teacher in a Bosnian village; twenty-nine, gentle, clever and pretty, with a love affair and an apartment of her own. Until one spring day a young Serb soldier walks uninvited into her kitchen and tells her to pack her bag, and her life is interrupted. As the sky turns black with smoke behind her, S. enters a new world, where peace is a fairytale and there are no homes but only camps: transit camps, reception camps, labour camps, death camps.”

Still in her kitchen, at first S. is too shocked to do anything but offer the soldier a cup of coffee. She had known something terrible was about to happen, all the signs were there. There was time to flee, but she’d clung to a hope that it wouldn’t be necessary. She didn’t want to give up her familiar, ordinary, happy life.

S. ends up in a camp where she is repeatedly raped and tortured. She falls pregnant. After liberation, in exile in Sweden, she gives birth to a child whom she decides to keep and nurture. Slavenka Drakulić’s novel is fictitious; it doesn’t tell the story of any particular woman, but it is the story of thousands of women in the Balkans, of women all around the world. In your nightmares, it is your story.

***

Under extreme pressure, you imagine how relatively easy it would be to return to Geretsdorf or Salzburg, to make a new-old life for yourself and your husband there. In these visions you see yourself taking him by the hand, grabbing your passports, putting your cats in their transport cages and taking the quickest route to the Austrian consulate or directly to the airport. In your mind, you are ready to pack and go anytime. You’ve done it in the past, as an Eastern European refugee, moving from one place to another, always in a hurry, hardly ever allowed to take anything with you. You know you can survive.

***

Ultimately, nothing can happen without loss. Two things represent all: a language and a bed. You fear the necessity of having constantly to negotiate between a husband and a lover. You have made your bed, and now you want to sleep in it. The affair is too passionate and precious to end. You do not want the practicalities of living in a German-speaking world to invade this space. You fear your adulterous mind, knowing how flippantly it had switched before, making you dream, think, live in another language. But it had never been as creative as in English, in this turbulent, divided country that you call home.

Yes, you choose to continue waking up from nightmares next to your husband and your cats in your old Victorian brass bed – this silent witness to over a century of marital bliss, estrangement, passion and loneliness. This is the place where your family gathers, where you sleep, make love, eat, watch rugby on TV, read, laugh, talk, pick your way around the cats. Where you listen to the sounds of the house and the constant low hum of the city at night, fearing malevolent footsteps.

Should you ever decide or be forced to leave, the bed – and almost everything else – would have to stay.

***

You aren’t good at dealing with this kind of loss. You grow instantly attached to objects. You surround yourself with charms, dream-catchers; Rudolf, your small, plush guardian angel, never leaves your side; hundreds of books (As If I Am Not There among them), clothes (the black top you found in Aberystwyth), mugs you collect (the tall handmade dark-blue one from the Norwegian island Ona), furniture (mostly bookshelves), a few jewels (the silver peacock brooch with turquoise stones from your grandma), photographs (of you with your husband and Madiba), shoes (the beige slippers from Paris), paintings (a Jan Vermeiren commissioned by your husband for your twenty-ninth birthday), mirrors (the one that waited a year for you at the Naked Truth in Stellenbosch), a laptop (with your creative output saved in it), cameras (both from your father), the camera bag from your mother, the stuffed rag rat your Aunt Iwona made for your namesday when you were fourteen, the circle-of-friends candleholder from your best friend Isabella, the Swatch your father gave you fifteen years ago, the Winnie-the-Pooh eraser from your brother, and the white lace tablecloth from your great aunt. These items are worthless, but priceless. Like your small Daihatsu, standing unlocked in front of your windows, you want to keep it all, to collect it even in writing.

But whereas you don’t have to worry about the little car or anything else you own in Austria, all these precious possessions are in danger in Cape Town, if not of being stolen (who would want you great aunt’s lace tablecloth?), then of being left behind if worst comes to worst. The mere idea of it makes you ache inside. You want to curl up somewhere safe and not think about it. Throughout your migratory childhood and youth you didn’t allow yourself to grow too attached to people; it was safer to grow attached to the few things you could carry.

The Victorian brass bed in Cape Town embodies your new-found creativity. The thought of losing it fills you with a dread greater than the fear of finding a soldier in your kitchen. You understand S., even though nothing about all this is rational. You are a bundle of intuitions and anxieties. Split in half, you know you should be leaving, and yet you insist on staying on your island, hoping against hope, against all facts, against the statistics of the reality around you. Instead you dream, love, laugh and put your creative energies to good uses. Every day, you stand on your stoep and look up at Devil’s Peak and know you will never want to trade it for a medieval fortress. And in the small hours of the night, you lie awake in the brass bed, waiting for your soldier to come, to serve him coffee.

***

‘Dziecko, kolacja gotowa.’ (Child, dinner’s ready.) Your mother calls from upstairs and you look at your Swatch; it’s eight. You get up from behind your desk and, hugging the dedicated book to your heart, you close the terrace door with your right hand to keep the mosquitoes out at night. It is almost dark, the sky the colour of spilt ink. Your Daihatsu looks grey in the twilight. The emerald arborvitae hedge your parents planted around their new property is almost as tall as the old one in Braunau, but you can still see the lights going on in your neighbour’s house across the street. After dinner you will call your husband at home and wish him goodnight. You will miss him and the cats for the next ten days of your visit. You will have a bubble bath with an Uttendorfer. The practical IKEA double bed you have in Geretsdorf will seem empty and cold, even in the middle of summer. You will read before falling asleep, marvelling at the silence of the countryside around you. You will be preoccupied with the corrections to an essay about the recent xenophobic attacks in the country; there will be no foreign footsteps invading these thoughts. When your light is off and the silence absolute, nobody and nothing will disturb your dreams about your old Victorian bed in Cape Town.

***

I am like you. It’s terrifying.

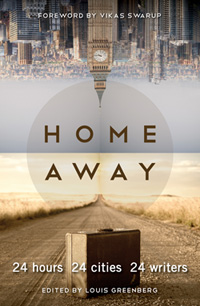

First published in Home Away, edited by Louis Greenberg (Zebra Press, 2010).