I would have bought Don DeLillo’s latest novel, Zero K, just for the exquisite, elegant cover. However, the nostalgia I feel for the author of the book ever since I read his stunning White Noise (1985) at university was its strongest selling point.

The essence of the title, the slick prose, the reduction of plot to bare essentials, the narrative’s minimalist beauty are all reflected in the cover design. You get what you see. The story is seemingly simple: billionaire Ross Lockhart invests in Convergence, a futuristic secret place somewhere in Asia where people are allowed to die on their own terms. They are kept in a state of stasis with the hope of being reawakened at a distant point in time when whatever ailed them can be overcome.

Artis, Lockhart’s second wife, is terminally ill and has decided to undergo the procedure. Ross asks Jeff, his only son from his first marriage to Madeline, to witness the transition. Deeply in love with Artis, in a moment of longing and desperation, Ross chooses to join his spouse, but then other considerations complicate the decision. Artis herself reveals a wish which throws Jeff off balance.

Jeff remembers his mother and her torturous death from cancer after Ross had left the family when the boy was still growing up. The relationship with his father is distant and troubled. Jeff’s entire adult life is a counter reaction to his father’s abandonment and ambitions. Now in his early thirties, Jeff is simultaneously confronted with the past they share and the future his father imagines.

In Convergence their fears and desires collide. The compound’s artistic design is a stark reminder of all that is sublime and evil in the world. The one does not seem to be able to exist without the other. It is a space of contemplation and a certain type of finality which offers the beyond so many dream of. But in what kind of world would we really be prepared to face eternity? Surely not the deteriorating, plagued, violent planet of our own making, the one we currently so carelessly refer to as home. The ancient question persists: “What’s the point of living if we don’t die at the end of it?” Is a surrender in which we gain instead of relinquish control and power worthwhile?

Zero K – the title derives from “a unit of temperature called absolute zero” – is a powerful meditation on life, the current state of global affairs and our uncertain future. The only thing I could fault it for is the weary sterility of the emotions it stirs, but then again: it reflects much of what we have come to accept about our fragile world: “I knew what I was feeling, a sympathy bled white by disappointment.” Only a few of us notice one of those moments “never to be thought of except when it’s in the process of unfolding.” And it will be our novelists and artists who will keep reminding us what is at stake.

Zero K

by Don DeLillo

Picador, 2016

First published in the Cape Times, 6 January 2017.

In an act of idiotic drunken bravery, two friends, Tom and Vale, steal a boat in a storm. The consequences for both of them are enormous. The incident lays bare a past supressed for a decade and a future which is just as heavy to carry. The laden, rain-drenched darkness of the night of the theft sets the tone for this atmospheric narrative. Fiona Melrose’s stunning debut novel Midwinter tells the story of loss, the way it breaks you down and the effort it takes to put together the shattered pieces.

In an act of idiotic drunken bravery, two friends, Tom and Vale, steal a boat in a storm. The consequences for both of them are enormous. The incident lays bare a past supressed for a decade and a future which is just as heavy to carry. The laden, rain-drenched darkness of the night of the theft sets the tone for this atmospheric narrative. Fiona Melrose’s stunning debut novel Midwinter tells the story of loss, the way it breaks you down and the effort it takes to put together the shattered pieces. The author should also be commended for doing what much too often writers shy away from: writing entirely from a (gender) perspective which is not their own. At no time in the novel did I ever feel that I was not in the heads and hearts of a young man and his ageing father. Melrose uses first-person narrators for both to great effect: “For ten years I’d shirked the memories. I always felt them scratching at the darker corners of my mind, still feral; but sitting on a tree stump in the gathering dark, all of it – the space, the fear, the sorrow – all seemed to find me again.”

The author should also be commended for doing what much too often writers shy away from: writing entirely from a (gender) perspective which is not their own. At no time in the novel did I ever feel that I was not in the heads and hearts of a young man and his ageing father. Melrose uses first-person narrators for both to great effect: “For ten years I’d shirked the memories. I always felt them scratching at the darker corners of my mind, still feral; but sitting on a tree stump in the gathering dark, all of it – the space, the fear, the sorrow – all seemed to find me again.” Travelling in India, Karen Jennings visits an art gallery where “holograms of rare gold artefacts line the wall. A notice declares that precious items might be stolen and so holograms are the next best thing. They are fuzzy, unclear. It is like looking at an object at the bottom of a dirty pond.” It is a striking image that made me think of writing an autobiographical novel or a memoir. In the hands of a mediocre writer, recollections and artefacts can become like these blurred holograms. But Karen Jennings is not a mediocre writer.

Travelling in India, Karen Jennings visits an art gallery where “holograms of rare gold artefacts line the wall. A notice declares that precious items might be stolen and so holograms are the next best thing. They are fuzzy, unclear. It is like looking at an object at the bottom of a dirty pond.” It is a striking image that made me think of writing an autobiographical novel or a memoir. In the hands of a mediocre writer, recollections and artefacts can become like these blurred holograms. But Karen Jennings is not a mediocre writer.

The Bostik Book of Unbelievable Beasties

The Bostik Book of Unbelievable Beasties Cats

Cats Reading a play is like listening to an opera on CD. Many would argue that both are best experienced on stage. There is nothing like a live performance, I agree. Yet, no matter how much I love going to the theatre or opera house, reading a play or listening to opera in the comfort of my own home can also be special.

Reading a play is like listening to an opera on CD. Many would argue that both are best experienced on stage. There is nothing like a live performance, I agree. Yet, no matter how much I love going to the theatre or opera house, reading a play or listening to opera in the comfort of my own home can also be special. Dream of the Dog was first written and appeared as a local radio play in 2006, and was rewritten and staged the following year in South Africa before transferring overseas. Its action takes place in KwaZulu-Natal. An aging couple sell their farm to developers. The man in charge of the project turns out to be the son of one of their former workers. As he returns to the place, he brings with him long-supressed memories of violence and death on the farm. The play inspired Higginson’s latest novel, The Dream House (2015), which won the prestigious

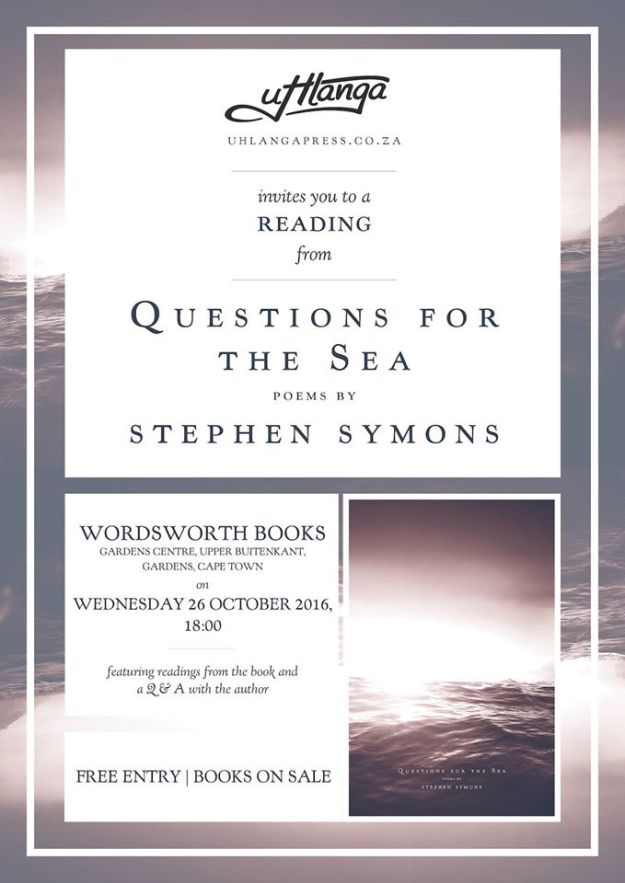

Dream of the Dog was first written and appeared as a local radio play in 2006, and was rewritten and staged the following year in South Africa before transferring overseas. Its action takes place in KwaZulu-Natal. An aging couple sell their farm to developers. The man in charge of the project turns out to be the son of one of their former workers. As he returns to the place, he brings with him long-supressed memories of violence and death on the farm. The play inspired Higginson’s latest novel, The Dream House (2015), which won the prestigious  Questions for the Sea, the debut collection by Cape Town-based poet and graphic designer Stephen Symons is the latest exquisite offering from the independent local publisher, uHlanga. The sea, questions, light and poetry: an irresistible combination.

Questions for the Sea, the debut collection by Cape Town-based poet and graphic designer Stephen Symons is the latest exquisite offering from the independent local publisher, uHlanga. The sea, questions, light and poetry: an irresistible combination.

I welcome every Susan Fletcher novel with open arms. Let Me Tell You About a Man I Knew is her sixth. It completely delivers on the promise of its predecessors. Set in the Provencal town of Saint-Rémy where Vincent van Gogh spent a year of his life in an asylum and painted some of his most widely recognised works, the novel tells the story of a local woman whose life is disrupted by the arrival of the Dutch painter. Jeanne Trabuc is the wife of the asylum’s warden. In her fifties, a mother of three, she goes about her daily routines, remembering her adventurous youth and watching out for the mistral, “wind of change, of shallow sleep.”

I welcome every Susan Fletcher novel with open arms. Let Me Tell You About a Man I Knew is her sixth. It completely delivers on the promise of its predecessors. Set in the Provencal town of Saint-Rémy where Vincent van Gogh spent a year of his life in an asylum and painted some of his most widely recognised works, the novel tells the story of a local woman whose life is disrupted by the arrival of the Dutch painter. Jeanne Trabuc is the wife of the asylum’s warden. In her fifties, a mother of three, she goes about her daily routines, remembering her adventurous youth and watching out for the mistral, “wind of change, of shallow sleep.” Throughout the years, few oeuvres have enriched my intellectual life as much as the works of the Welsh philosopher Mark Rowlands. At some stage, we are all confronted with the question of what makes life worthwhile, how to make the time we have on this planet meaningful. Unfortunately, not enough of us ask how to live in such a way as not only to enjoy the journey, but simultaneously do as little harm as possible to our fellow travellers, whether they be other humans, animals or the environment. We all muddle on. Rowlands does not claim to have the answers, but his attempts at approaching possible conclusions are fascinating to engage with.

Throughout the years, few oeuvres have enriched my intellectual life as much as the works of the Welsh philosopher Mark Rowlands. At some stage, we are all confronted with the question of what makes life worthwhile, how to make the time we have on this planet meaningful. Unfortunately, not enough of us ask how to live in such a way as not only to enjoy the journey, but simultaneously do as little harm as possible to our fellow travellers, whether they be other humans, animals or the environment. We all muddle on. Rowlands does not claim to have the answers, but his attempts at approaching possible conclusions are fascinating to engage with.

It is December 1907 in Tsau, Bechuanaland, after the Herero and Namaqua genocide perpetrated by the Germans occupying German South-West Africa, today’s Namibia. The Herero couple Tjipuka and Ruhapo have survived “the scattering”, but lost nearly everything in the process. When we first encounter them, they are together, but terrifyingly estranged. Tjipuka traces her husband’s body, trying to remember all that she’d loved about it, but the memories are overshadowed by his distance and the blood and cruelty of lies which haunt them: “Being dead made a lot of things uncertain.”

It is December 1907 in Tsau, Bechuanaland, after the Herero and Namaqua genocide perpetrated by the Germans occupying German South-West Africa, today’s Namibia. The Herero couple Tjipuka and Ruhapo have survived “the scattering”, but lost nearly everything in the process. When we first encounter them, they are together, but terrifyingly estranged. Tjipuka traces her husband’s body, trying to remember all that she’d loved about it, but the memories are overshadowed by his distance and the blood and cruelty of lies which haunt them: “Being dead made a lot of things uncertain.” The title of Nthikeng Mohlele’s fourth novel delivers on its promise. Pleasure is a mesmerising, unusual book. At times I was hesitant to call it a novel. The story of Milton Mohlele, his dreams and musings, which he attempts to distil into writing, reads like a meditation. As literary history echoes in his name, Milton could be an alter ego for most writers seeking to find not only meaning but pleasure in the written word – to capture that elusive something which makes us sigh deeply with content when, if ever, we truly encounter it.

The title of Nthikeng Mohlele’s fourth novel delivers on its promise. Pleasure is a mesmerising, unusual book. At times I was hesitant to call it a novel. The story of Milton Mohlele, his dreams and musings, which he attempts to distil into writing, reads like a meditation. As literary history echoes in his name, Milton could be an alter ego for most writers seeking to find not only meaning but pleasure in the written word – to capture that elusive something which makes us sigh deeply with content when, if ever, we truly encounter it.