I was born in Poland, but as a student I used to live in Wales. About two years ago, I read a glowing review of Everything I Found on the Beach by the young Welsh writer Cynan Jones. The reviewer mentioned that the novel featured a Polish character. A Welsh novel with a Polish character was an irresistible combination for a reader with my literary background. I ordered and devoured it, and since then I have read every other novel or novella I could get hold of by the same author: The Long Dry, The Dig, and the latest, Cove.

I was born in Poland, but as a student I used to live in Wales. About two years ago, I read a glowing review of Everything I Found on the Beach by the young Welsh writer Cynan Jones. The reviewer mentioned that the novel featured a Polish character. A Welsh novel with a Polish character was an irresistible combination for a reader with my literary background. I ordered and devoured it, and since then I have read every other novel or novella I could get hold of by the same author: The Long Dry, The Dig, and the latest, Cove.

Cynan Jones has become one of my favourite writers and I await each new book of his with fervent anticipation. I have never been disappointed. His work offers two elements which I find most exciting in literature: the ability to lay bare the intricate landscapes of the human heart and soul, and a prose powerful enough to match what is revealed: the brutality and beauty of our existence. Jones is constantly being compared with the greats of modern literature – rightly so. But his voice is distinct, unforgettable.

Cove opens on a beach. A child is missing. A doll is washed up by the tide. And a dead pigeon is found: “The head was gone, the meat of its chest. The breast-bone oddly, industriously clean.” The man who finds it feels a sense of horror that the bird “knew before being struck. Of it trying to get home. Of something throwing it off course.” He removes the rings from its leg to return them to the owner who will be wondering about its fate.

As the epigraph explains, a cove can be “a small bay or inlet; a sheltered place” or “a fellow; a man”. Cove tells the story of a man who finds himself adrift in a kayak after he is struck by lightning. His recollections of how he got there and who he is are vague. He is injured, covered in ashes: the remains of someone who will definitely not return. The shore seems unreachable, but intuitively he knows that someone is waiting for him to come back: “The idea of her, whoever she might be, seemed to grow into a point on the horizon he could aim for.”

Cove is a quest for survival – man versus the elements: “Stay alive, he thinks.” Jones knows how to tell unique stories with universal appeal. He is fearless in his explorations of places most of us are terrified of. As in life, death is a constant in his stories. He reduces his plots to essentials and by doing so magnifies what is truly important. His work reminds us of the strengths and brilliance of the novella, an underestimated form in our time.

When you face the impossible, and all seems wrecked and lost, not many options remain: “If you disappear you will grow into a myth for them. You will exist only as absence. If you get back, you will exist as a legend.”

Cove

by Cynan Jones

Granta, 2016

Review first published in the Cape Times, 13 January 2017.

In an act of idiotic drunken bravery, two friends, Tom and Vale, steal a boat in a storm. The consequences for both of them are enormous. The incident lays bare a past supressed for a decade and a future which is just as heavy to carry. The laden, rain-drenched darkness of the night of the theft sets the tone for this atmospheric narrative. Fiona Melrose’s stunning debut novel Midwinter tells the story of loss, the way it breaks you down and the effort it takes to put together the shattered pieces.

In an act of idiotic drunken bravery, two friends, Tom and Vale, steal a boat in a storm. The consequences for both of them are enormous. The incident lays bare a past supressed for a decade and a future which is just as heavy to carry. The laden, rain-drenched darkness of the night of the theft sets the tone for this atmospheric narrative. Fiona Melrose’s stunning debut novel Midwinter tells the story of loss, the way it breaks you down and the effort it takes to put together the shattered pieces. The author should also be commended for doing what much too often writers shy away from: writing entirely from a (gender) perspective which is not their own. At no time in the novel did I ever feel that I was not in the heads and hearts of a young man and his ageing father. Melrose uses first-person narrators for both to great effect: “For ten years I’d shirked the memories. I always felt them scratching at the darker corners of my mind, still feral; but sitting on a tree stump in the gathering dark, all of it – the space, the fear, the sorrow – all seemed to find me again.”

The author should also be commended for doing what much too often writers shy away from: writing entirely from a (gender) perspective which is not their own. At no time in the novel did I ever feel that I was not in the heads and hearts of a young man and his ageing father. Melrose uses first-person narrators for both to great effect: “For ten years I’d shirked the memories. I always felt them scratching at the darker corners of my mind, still feral; but sitting on a tree stump in the gathering dark, all of it – the space, the fear, the sorrow – all seemed to find me again.” The overwhelming impression I had while reading Abner Nyamende’s There’s always tomorrow was that the novel had not been edited properly, if at all. It began with the first page, where the word “darkness” features six times without apparent reason. And the unnecessary repetitions are only the tip of the iceberg. After finishing, out of curiosity I looked up Partridge, the publishing house, and was informed that, although backed by a giant international trade publisher, the company provides only self-publishing services to their authors. Editing seems to be part of the professional packages on offer, but I cannot imagine that it was employed in this particular case. In this regard I was appalled at the quality of the final product, and it is a pity, because the book has an important story to tell. If the author did pay for editing of any kind, he was cheated…

The overwhelming impression I had while reading Abner Nyamende’s There’s always tomorrow was that the novel had not been edited properly, if at all. It began with the first page, where the word “darkness” features six times without apparent reason. And the unnecessary repetitions are only the tip of the iceberg. After finishing, out of curiosity I looked up Partridge, the publishing house, and was informed that, although backed by a giant international trade publisher, the company provides only self-publishing services to their authors. Editing seems to be part of the professional packages on offer, but I cannot imagine that it was employed in this particular case. In this regard I was appalled at the quality of the final product, and it is a pity, because the book has an important story to tell. If the author did pay for editing of any kind, he was cheated… Travelling in India, Karen Jennings visits an art gallery where “holograms of rare gold artefacts line the wall. A notice declares that precious items might be stolen and so holograms are the next best thing. They are fuzzy, unclear. It is like looking at an object at the bottom of a dirty pond.” It is a striking image that made me think of writing an autobiographical novel or a memoir. In the hands of a mediocre writer, recollections and artefacts can become like these blurred holograms. But Karen Jennings is not a mediocre writer.

Travelling in India, Karen Jennings visits an art gallery where “holograms of rare gold artefacts line the wall. A notice declares that precious items might be stolen and so holograms are the next best thing. They are fuzzy, unclear. It is like looking at an object at the bottom of a dirty pond.” It is a striking image that made me think of writing an autobiographical novel or a memoir. In the hands of a mediocre writer, recollections and artefacts can become like these blurred holograms. But Karen Jennings is not a mediocre writer. Reading a play is like listening to an opera on CD. Many would argue that both are best experienced on stage. There is nothing like a live performance, I agree. Yet, no matter how much I love going to the theatre or opera house, reading a play or listening to opera in the comfort of my own home can also be special.

Reading a play is like listening to an opera on CD. Many would argue that both are best experienced on stage. There is nothing like a live performance, I agree. Yet, no matter how much I love going to the theatre or opera house, reading a play or listening to opera in the comfort of my own home can also be special. Dream of the Dog was first written and appeared as a local radio play in 2006, and was rewritten and staged the following year in South Africa before transferring overseas. Its action takes place in KwaZulu-Natal. An aging couple sell their farm to developers. The man in charge of the project turns out to be the son of one of their former workers. As he returns to the place, he brings with him long-supressed memories of violence and death on the farm. The play inspired Higginson’s latest novel, The Dream House (2015), which won the prestigious

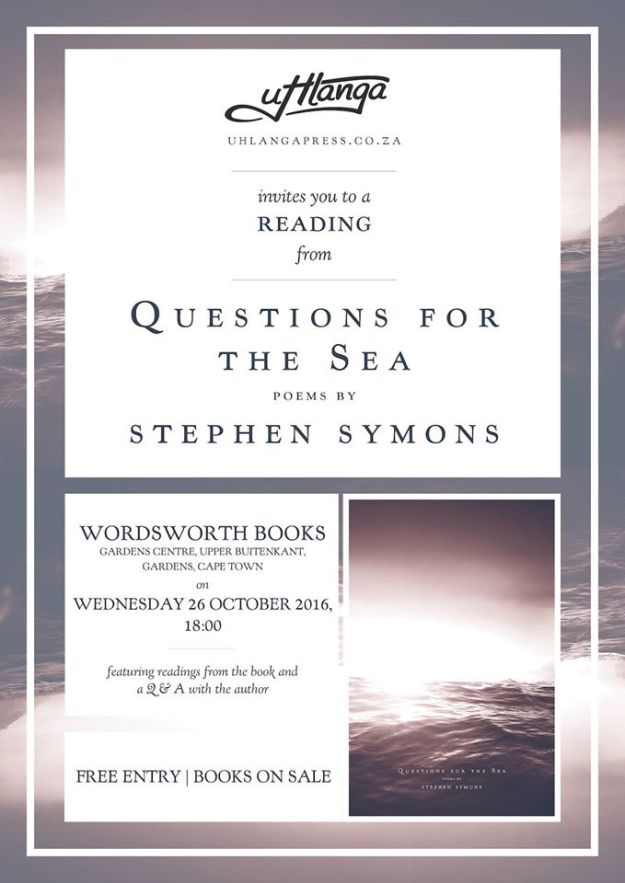

Dream of the Dog was first written and appeared as a local radio play in 2006, and was rewritten and staged the following year in South Africa before transferring overseas. Its action takes place in KwaZulu-Natal. An aging couple sell their farm to developers. The man in charge of the project turns out to be the son of one of their former workers. As he returns to the place, he brings with him long-supressed memories of violence and death on the farm. The play inspired Higginson’s latest novel, The Dream House (2015), which won the prestigious  Questions for the Sea, the debut collection by Cape Town-based poet and graphic designer Stephen Symons is the latest exquisite offering from the independent local publisher, uHlanga. The sea, questions, light and poetry: an irresistible combination.

Questions for the Sea, the debut collection by Cape Town-based poet and graphic designer Stephen Symons is the latest exquisite offering from the independent local publisher, uHlanga. The sea, questions, light and poetry: an irresistible combination.

For a white person, reading Writing What We Like: A New Generation Speaks might feel like gatecrashing a party where some ugly truths will be revealed about you. Provocative and penetrating, Writing What We Like is a difficult book to review when you happen to be white, because one feels that one should not be talking at all, but listening only. One is torn between possible accusations of one’s own “intellectual arrogance” and the need for dialogue. And yet, a way to disrupt entrenched ways of thinking and to establish connections across barriers imposed on us by a turbulent and harrowing history is to try to imagine ourselves into the skins of others. That is where creativity and empathy begin – in writing, reading and interpretation – where we cease to view ourselves in any other categories but human. The ultimate goal is understanding, coupled with compassion. Everything else will follow from there.

For a white person, reading Writing What We Like: A New Generation Speaks might feel like gatecrashing a party where some ugly truths will be revealed about you. Provocative and penetrating, Writing What We Like is a difficult book to review when you happen to be white, because one feels that one should not be talking at all, but listening only. One is torn between possible accusations of one’s own “intellectual arrogance” and the need for dialogue. And yet, a way to disrupt entrenched ways of thinking and to establish connections across barriers imposed on us by a turbulent and harrowing history is to try to imagine ourselves into the skins of others. That is where creativity and empathy begin – in writing, reading and interpretation – where we cease to view ourselves in any other categories but human. The ultimate goal is understanding, coupled with compassion. Everything else will follow from there. I welcome every Susan Fletcher novel with open arms. Let Me Tell You About a Man I Knew is her sixth. It completely delivers on the promise of its predecessors. Set in the Provencal town of Saint-Rémy where Vincent van Gogh spent a year of his life in an asylum and painted some of his most widely recognised works, the novel tells the story of a local woman whose life is disrupted by the arrival of the Dutch painter. Jeanne Trabuc is the wife of the asylum’s warden. In her fifties, a mother of three, she goes about her daily routines, remembering her adventurous youth and watching out for the mistral, “wind of change, of shallow sleep.”

I welcome every Susan Fletcher novel with open arms. Let Me Tell You About a Man I Knew is her sixth. It completely delivers on the promise of its predecessors. Set in the Provencal town of Saint-Rémy where Vincent van Gogh spent a year of his life in an asylum and painted some of his most widely recognised works, the novel tells the story of a local woman whose life is disrupted by the arrival of the Dutch painter. Jeanne Trabuc is the wife of the asylum’s warden. In her fifties, a mother of three, she goes about her daily routines, remembering her adventurous youth and watching out for the mistral, “wind of change, of shallow sleep.” Throughout the years, few oeuvres have enriched my intellectual life as much as the works of the Welsh philosopher Mark Rowlands. At some stage, we are all confronted with the question of what makes life worthwhile, how to make the time we have on this planet meaningful. Unfortunately, not enough of us ask how to live in such a way as not only to enjoy the journey, but simultaneously do as little harm as possible to our fellow travellers, whether they be other humans, animals or the environment. We all muddle on. Rowlands does not claim to have the answers, but his attempts at approaching possible conclusions are fascinating to engage with.

Throughout the years, few oeuvres have enriched my intellectual life as much as the works of the Welsh philosopher Mark Rowlands. At some stage, we are all confronted with the question of what makes life worthwhile, how to make the time we have on this planet meaningful. Unfortunately, not enough of us ask how to live in such a way as not only to enjoy the journey, but simultaneously do as little harm as possible to our fellow travellers, whether they be other humans, animals or the environment. We all muddle on. Rowlands does not claim to have the answers, but his attempts at approaching possible conclusions are fascinating to engage with.