Lara Feigel is a cultural historian and a literary critic, combining her interests to write about the meeting point between life, literature and history. In her last two books, she looks at how people whose quintessential purpose in life is the search for beauty and meaning survived their antithesis: war. In her The Love-charms of Bombs: Restless Lives in the Second World War (2013), Feigel wrote about five authors who were based in wartime London, driving ambulances, fighting fires, being creative, and loving passionately while desperately trying to remain alive.

Lara Feigel is a cultural historian and a literary critic, combining her interests to write about the meeting point between life, literature and history. In her last two books, she looks at how people whose quintessential purpose in life is the search for beauty and meaning survived their antithesis: war. In her The Love-charms of Bombs: Restless Lives in the Second World War (2013), Feigel wrote about five authors who were based in wartime London, driving ambulances, fighting fires, being creative, and loving passionately while desperately trying to remain alive.

In her latest offering, The Bitter Taste of Victory: Life, Love and Art in the Ruins of the Reich, Feigel picks up where she left off in her previous book, at the end of the war, and introduces a new, larger cast of characters – writers, intellectuals and artists – who were sent by the Allies to defeated and occupied Germany to assist in denazification and rebuilding the nation they had been trying systematically to annihilate over the past few years.

Their idealistic mission is an opportunity like no other, placing cultural activities at the centre of the plans to reconstruct the country. For a brief moment in history “a new united Europe, underpinned by shared heritage that would allow nationalism to be replaced by a common consciousness of collective humanity” seems like a viable option for the continent’s future.

Germany is a wasteland. Poverty, hunger and despair rule. Survivors grapple with guilt. Exiled German writer Peter de Mendelssohn arrives to establish newspapers in the British zone. He notes that “new eyes” and “totally new words” are needed to describe the devastation.

The horrors perpetrated in the concentration camps come to the surface of the world’s consciousness, and with them questions of complicity, responsibility and justice. In the light of the revelations and the Germans’ lack of immediate repentance, the Allied artists and reporters sent to the country find it nearly impossible to “make sense of the postwar world” or to emphasise with the people they encounter.

Among them is the photographer and war correspondent Lee Miller. After a visit to Dachau, she photographs herself in Hitler’s bathtub. Like others, she is “troubled by the ordinariness of Nazi leaders.” German-born Hollywood star Marlene Dietrich, “in army uniform, low-voiced, funny and adoring” has to face the fact that her family members collaborated with the Nazis.

Eerily echoing our own, this is the time of the Nurnberg trials, the nuclear bomb, migration, displacement and rising tensions between the other ideologies taking hold of post-war Europe, resulting in the division which will most strikingly manifest in the Berlin Wall. A sense of failure and helplessness sets in. But Feigel ends her brilliant portrayal of this turbulent period with Austrian-born Jewish American filmmaker Billy Wilder who “was able to laugh off the bureaucratic absurdity of communism, the megalomaniac blindness of American imperialism, and the fascist conformity of the Germans by satirising them all in equal measure” and standing “defiantly on the side of life.”

The Bitter Taste of Victory: Life, Love and Art in the Ruins of the Reich

by Lara Feigel

Bloomsbury, 2016

Review first published in the Cape Times, 24 February 2017.

Dene Smuts once said that “there are two approaches to opposition lawmaking work: making a noise and making a difference.” Throughout her courageous life she chose to make a difference. Smuts completed the manuscript of Patriots and Parasites: South Africa and the Struggle to Evade History shortly before her unexpected death in April last year. Her daughter Julia midwifed the project to completion.

Dene Smuts once said that “there are two approaches to opposition lawmaking work: making a noise and making a difference.” Throughout her courageous life she chose to make a difference. Smuts completed the manuscript of Patriots and Parasites: South Africa and the Struggle to Evade History shortly before her unexpected death in April last year. Her daughter Julia midwifed the project to completion. There are times when people proclaim either the death of reading, or the death of the book as a physical object, or the death of bookshops, and no matter how much sceptics try to kill off one of the most engaging and enriching human experiences, it prevails and with it does the book and its private and public homes: bookshops and libraries. As any passionate reader will verify, bookshops can be oases of literary bliss. Jorge Carrión travelled around the world to visit many of them and wrote a fervent reminder of why they matter: “Every bookshop is a condensed version of the world.” South African readers will delight in the mention of local authors and favourites places such as the

There are times when people proclaim either the death of reading, or the death of the book as a physical object, or the death of bookshops, and no matter how much sceptics try to kill off one of the most engaging and enriching human experiences, it prevails and with it does the book and its private and public homes: bookshops and libraries. As any passionate reader will verify, bookshops can be oases of literary bliss. Jorge Carrión travelled around the world to visit many of them and wrote a fervent reminder of why they matter: “Every bookshop is a condensed version of the world.” South African readers will delight in the mention of local authors and favourites places such as the  “Who would want to read them?” we are asked at the back of Marike Beyers’s poetry collection, How to Open the Door. The answer is as easy as it is true: “Anyone interested in the recent inflection of various Englishes and … inflections of the ‘soul’.” In deceptively simple words Beyers captures complex memories of family scenes and relationship dynamics, stretching across time and space. There is loss, tenderness and pain: “here I am all razor blades / and concrete rubble / all corners sharp”. She is just as aware of language as of silence: “but there you stood / your mouth of broken birds”. There are people who live “outside of words”, but not the poet; “is it all too simple / is home then / this standing // in an open door”, she asks, and invites us to follow into the space of her poetic vision.

“Who would want to read them?” we are asked at the back of Marike Beyers’s poetry collection, How to Open the Door. The answer is as easy as it is true: “Anyone interested in the recent inflection of various Englishes and … inflections of the ‘soul’.” In deceptively simple words Beyers captures complex memories of family scenes and relationship dynamics, stretching across time and space. There is loss, tenderness and pain: “here I am all razor blades / and concrete rubble / all corners sharp”. She is just as aware of language as of silence: “but there you stood / your mouth of broken birds”. There are people who live “outside of words”, but not the poet; “is it all too simple / is home then / this standing // in an open door”, she asks, and invites us to follow into the space of her poetic vision. The image on the cover of Prunings, Helen Moffett’s second collection of poetry, is an exquisite unfinished painting of a broom karee branch. The poems in the slim chapbook are similarly delicate and unusually fragmented. Together with her editor and founder of uHlanga Press, Nick Mulgrew, Moffett decided to display the editorial process of pruning the individual pieces, but also entire poems which were cut from the volume and yet are still included in square brackets with horizontal lines struck through them. It is work in progress on show. The final effect of this innovative collaboration is one of wonder. What is supposedly excluded is as powerful as what remains:

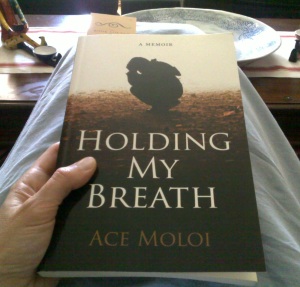

The image on the cover of Prunings, Helen Moffett’s second collection of poetry, is an exquisite unfinished painting of a broom karee branch. The poems in the slim chapbook are similarly delicate and unusually fragmented. Together with her editor and founder of uHlanga Press, Nick Mulgrew, Moffett decided to display the editorial process of pruning the individual pieces, but also entire poems which were cut from the volume and yet are still included in square brackets with horizontal lines struck through them. It is work in progress on show. The final effect of this innovative collaboration is one of wonder. What is supposedly excluded is as powerful as what remains:  Holding My Breath by Ace Moloi is a heart-wrenching, deeply inspirational grief memoir. Written in the form of a letter addressed to Moloi’s late mother, it tells his story before and after his mother’s death. He writes in the Prologue to the book: “I have decided to break the silence between us. I am starting this conversation to remind you of your younger son and to update you on my life.” Moloi points out that mourning is like learning a new language – “the language of living without you.” His mother died of an unexplained illness when he was thirteen and left him and his older brother to fend for themselves. Their father was absent when they were growing up. The boys had to rely on other family members for support. They encountered abandonment, hunger and despair as the divided family was mostly incapable of caring for them.

Holding My Breath by Ace Moloi is a heart-wrenching, deeply inspirational grief memoir. Written in the form of a letter addressed to Moloi’s late mother, it tells his story before and after his mother’s death. He writes in the Prologue to the book: “I have decided to break the silence between us. I am starting this conversation to remind you of your younger son and to update you on my life.” Moloi points out that mourning is like learning a new language – “the language of living without you.” His mother died of an unexplained illness when he was thirteen and left him and his older brother to fend for themselves. Their father was absent when they were growing up. The boys had to rely on other family members for support. They encountered abandonment, hunger and despair as the divided family was mostly incapable of caring for them.