I was born in Poland, but as a student I used to live in Wales. About two years ago, I read a glowing review of Everything I Found on the Beach by the young Welsh writer Cynan Jones. The reviewer mentioned that the novel featured a Polish character. A Welsh novel with a Polish character was an irresistible combination for a reader with my literary background. I ordered and devoured it, and since then I have read every other novel or novella I could get hold of by the same author: The Long Dry, The Dig, and the latest, Cove.

I was born in Poland, but as a student I used to live in Wales. About two years ago, I read a glowing review of Everything I Found on the Beach by the young Welsh writer Cynan Jones. The reviewer mentioned that the novel featured a Polish character. A Welsh novel with a Polish character was an irresistible combination for a reader with my literary background. I ordered and devoured it, and since then I have read every other novel or novella I could get hold of by the same author: The Long Dry, The Dig, and the latest, Cove.

Cynan Jones has become one of my favourite writers and I await each new book of his with fervent anticipation. I have never been disappointed. His work offers two elements which I find most exciting in literature: the ability to lay bare the intricate landscapes of the human heart and soul, and a prose powerful enough to match what is revealed: the brutality and beauty of our existence. Jones is constantly being compared with the greats of modern literature – rightly so. But his voice is distinct, unforgettable.

Cove opens on a beach. A child is missing. A doll is washed up by the tide. And a dead pigeon is found: “The head was gone, the meat of its chest. The breast-bone oddly, industriously clean.” The man who finds it feels a sense of horror that the bird “knew before being struck. Of it trying to get home. Of something throwing it off course.” He removes the rings from its leg to return them to the owner who will be wondering about its fate.

As the epigraph explains, a cove can be “a small bay or inlet; a sheltered place” or “a fellow; a man”. Cove tells the story of a man who finds himself adrift in a kayak after he is struck by lightning. His recollections of how he got there and who he is are vague. He is injured, covered in ashes: the remains of someone who will definitely not return. The shore seems unreachable, but intuitively he knows that someone is waiting for him to come back: “The idea of her, whoever she might be, seemed to grow into a point on the horizon he could aim for.”

Cove is a quest for survival – man versus the elements: “Stay alive, he thinks.” Jones knows how to tell unique stories with universal appeal. He is fearless in his explorations of places most of us are terrified of. As in life, death is a constant in his stories. He reduces his plots to essentials and by doing so magnifies what is truly important. His work reminds us of the strengths and brilliance of the novella, an underestimated form in our time.

When you face the impossible, and all seems wrecked and lost, not many options remain: “If you disappear you will grow into a myth for them. You will exist only as absence. If you get back, you will exist as a legend.”

Cove

by Cynan Jones

Granta, 2016

Review first published in the Cape Times, 13 January 2017.

Founded and headed by author Sarah McGregor, Clockwork Books is a new independent local publisher with a growing list of fascinating titles. Its latest release is Pamela Power’s second novel, Things Unseen, a psychological thriller set in the posh suburbs of Johannesburg. I first read it in manuscript form, and remember that I had to pause and take a deep breath after the shocking violence of the opening scene in which we witness the terrifying demise of a person and an animal. Let’s just say that the rest of the book is also not for sissies.

Founded and headed by author Sarah McGregor, Clockwork Books is a new independent local publisher with a growing list of fascinating titles. Its latest release is Pamela Power’s second novel, Things Unseen, a psychological thriller set in the posh suburbs of Johannesburg. I first read it in manuscript form, and remember that I had to pause and take a deep breath after the shocking violence of the opening scene in which we witness the terrifying demise of a person and an animal. Let’s just say that the rest of the book is also not for sissies. The overwhelming impression I had while reading Abner Nyamende’s There’s always tomorrow was that the novel had not been edited properly, if at all. It began with the first page, where the word “darkness” features six times without apparent reason. And the unnecessary repetitions are only the tip of the iceberg. After finishing, out of curiosity I looked up Partridge, the publishing house, and was informed that, although backed by a giant international trade publisher, the company provides only self-publishing services to their authors. Editing seems to be part of the professional packages on offer, but I cannot imagine that it was employed in this particular case. In this regard I was appalled at the quality of the final product, and it is a pity, because the book has an important story to tell. If the author did pay for editing of any kind, he was cheated…

The overwhelming impression I had while reading Abner Nyamende’s There’s always tomorrow was that the novel had not been edited properly, if at all. It began with the first page, where the word “darkness” features six times without apparent reason. And the unnecessary repetitions are only the tip of the iceberg. After finishing, out of curiosity I looked up Partridge, the publishing house, and was informed that, although backed by a giant international trade publisher, the company provides only self-publishing services to their authors. Editing seems to be part of the professional packages on offer, but I cannot imagine that it was employed in this particular case. In this regard I was appalled at the quality of the final product, and it is a pity, because the book has an important story to tell. If the author did pay for editing of any kind, he was cheated… Travelling in India, Karen Jennings visits an art gallery where “holograms of rare gold artefacts line the wall. A notice declares that precious items might be stolen and so holograms are the next best thing. They are fuzzy, unclear. It is like looking at an object at the bottom of a dirty pond.” It is a striking image that made me think of writing an autobiographical novel or a memoir. In the hands of a mediocre writer, recollections and artefacts can become like these blurred holograms. But Karen Jennings is not a mediocre writer.

Travelling in India, Karen Jennings visits an art gallery where “holograms of rare gold artefacts line the wall. A notice declares that precious items might be stolen and so holograms are the next best thing. They are fuzzy, unclear. It is like looking at an object at the bottom of a dirty pond.” It is a striking image that made me think of writing an autobiographical novel or a memoir. In the hands of a mediocre writer, recollections and artefacts can become like these blurred holograms. But Karen Jennings is not a mediocre writer.

The Bostik Book of Unbelievable Beasties

The Bostik Book of Unbelievable Beasties Cats

Cats

Reading a play is like listening to an opera on CD. Many would argue that both are best experienced on stage. There is nothing like a live performance, I agree. Yet, no matter how much I love going to the theatre or opera house, reading a play or listening to opera in the comfort of my own home can also be special.

Reading a play is like listening to an opera on CD. Many would argue that both are best experienced on stage. There is nothing like a live performance, I agree. Yet, no matter how much I love going to the theatre or opera house, reading a play or listening to opera in the comfort of my own home can also be special. Dream of the Dog was first written and appeared as a local radio play in 2006, and was rewritten and staged the following year in South Africa before transferring overseas. Its action takes place in KwaZulu-Natal. An aging couple sell their farm to developers. The man in charge of the project turns out to be the son of one of their former workers. As he returns to the place, he brings with him long-supressed memories of violence and death on the farm. The play inspired Higginson’s latest novel, The Dream House (2015), which won the prestigious

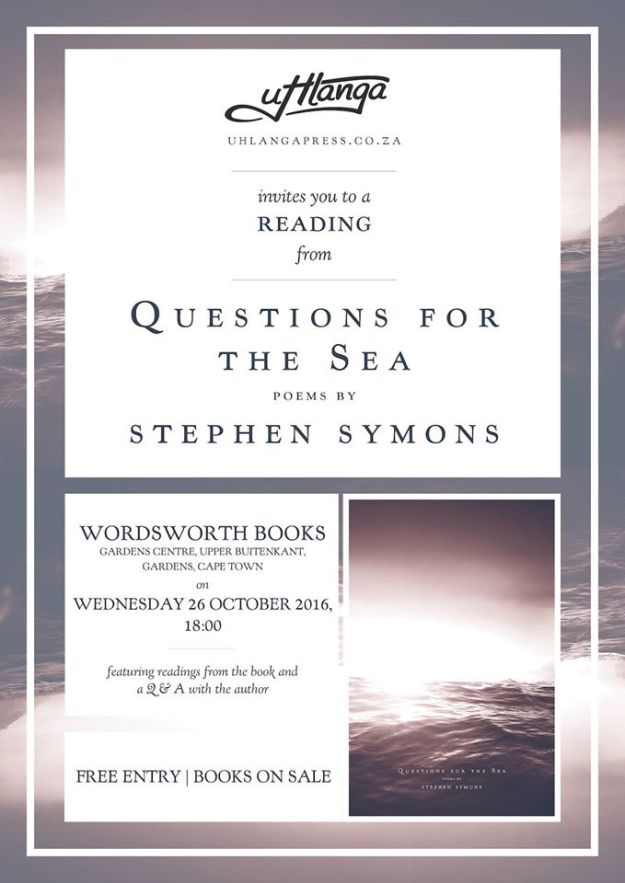

Dream of the Dog was first written and appeared as a local radio play in 2006, and was rewritten and staged the following year in South Africa before transferring overseas. Its action takes place in KwaZulu-Natal. An aging couple sell their farm to developers. The man in charge of the project turns out to be the son of one of their former workers. As he returns to the place, he brings with him long-supressed memories of violence and death on the farm. The play inspired Higginson’s latest novel, The Dream House (2015), which won the prestigious  Questions for the Sea, the debut collection by Cape Town-based poet and graphic designer Stephen Symons is the latest exquisite offering from the independent local publisher, uHlanga. The sea, questions, light and poetry: an irresistible combination.

Questions for the Sea, the debut collection by Cape Town-based poet and graphic designer Stephen Symons is the latest exquisite offering from the independent local publisher, uHlanga. The sea, questions, light and poetry: an irresistible combination.

Camaraderie. That is the word which comes to mind when I think back to the one day I spent at the fabulous Soweto Theatre, attending the inaugural The Star Soweto Literary Festival. It was quite a whirlwind affair. A day of talks, improvisation, laughter and tears. I invited myself. The moment I heard that the festival was happening – and it was organised in a shockingly short amount of time – I volunteered to speak, chair sessions, whatever, just to be there. I felt it in my bones that it would be special, and I wanted to be part of it.

Camaraderie. That is the word which comes to mind when I think back to the one day I spent at the fabulous Soweto Theatre, attending the inaugural The Star Soweto Literary Festival. It was quite a whirlwind affair. A day of talks, improvisation, laughter and tears. I invited myself. The moment I heard that the festival was happening – and it was organised in a shockingly short amount of time – I volunteered to speak, chair sessions, whatever, just to be there. I felt it in my bones that it would be special, and I wanted to be part of it. The day I was there, Saturday, the presence of the spirits of these literary giants was palpable. The attempt to establish “a truly non-racial” space for writers, artists and the public to engage with one another’s ideas was a great success. I attended with a dear friend, Pamela Power, the author of Ms Conception and the upcoming psychological thriller, Things Unseen. We came away inspired, glowing, and moved to the core.

The day I was there, Saturday, the presence of the spirits of these literary giants was palpable. The attempt to establish “a truly non-racial” space for writers, artists and the public to engage with one another’s ideas was a great success. I attended with a dear friend, Pamela Power, the author of Ms Conception and the upcoming psychological thriller, Things Unseen. We came away inspired, glowing, and moved to the core.