The relationship between domestic workers and their employers in South Africa has a complex and deeply troubled history. Yet, it lies at the heart of many local homes, whichever side of this relationship you find yourself on: as job creator or taker. The connection between the two defines everyday life for millions of South Africans. For foreigners, it is often unfathomable. Thus, I found Ena Jansen’s study of the subject, Like Family: Domestic Workers in South African History and Literature, extremely illuminating.

The relationship between domestic workers and their employers in South Africa has a complex and deeply troubled history. Yet, it lies at the heart of many local homes, whichever side of this relationship you find yourself on: as job creator or taker. The connection between the two defines everyday life for millions of South Africans. For foreigners, it is often unfathomable. Thus, I found Ena Jansen’s study of the subject, Like Family: Domestic Workers in South African History and Literature, extremely illuminating.

Having grown up in a Polish working-class family, I was taught to do all domestic work myself. Also, there was a time in my life when I cleaned other people’s houses to make money, but the transactions with my employers – cash for services rendered – did not involve much socio-historical baggage. Despite, or maybe because of, these experiences, after first moving to Cape Town, I found it incredibly difficult to adjust to having staff in the home I shared for a decade with my late husband. I now live alone and have returned to taking care of my home and garden on my own, finding it easier to negotiate. But I understand that my situation is exceptional within the context of South African history; I only know one other middle-class household where a domestic worker is not employed to clean up after the family.

My personal recollections and observations might seem irrelevant as such, but they point to the greatest achievement of Jansen’s book: no matter what else, Like Family will make you re-examine your position in this historically fraught set-up. Jansen herself recalls the women who took care of her and her family throughout their lives and invites her readers to reflect on their own situations through the prisms of South African history and literature.

First published in Afrikaans in 2015, Like Family has been updated and now includes references to more recent publications. By tracing the relationship between families and the people they either forced or employed to do their domestic work from mid-17th century to the present, Jansen unearths the origins of what the narrator of Barbara Fölscher’s short story “Kinders grootmaak is nie pap en melk nie” (Raising children is not simply a matter of porridge and milk, 2002) calls “a wound in my house”. It is a striking image, and most apt to illustrate the dynamics of violence, uncertainty and suffering that characterise the relationship and its background.

Rooted in slavery, the ties between domestic workers and their employers have undergone many changes in South Africa and resulted in a “peculiar, often contradictory form of duty and dependence”. Jansen sees the relationship as defining in comprehending race, class and gender relations in South Africa. Like Family is not a comfortable read, but its insights have the potential to change lives.

Like Family: Domestic Workers in South African History and Literature

Ena Jansen

Wits UP, 2019

Review first published in the Cape Times on 21 June 2019.

Zikr is the debut poetry collection of the writer and photographer Saaleha Idrees Bamjee. Once opened, it is not a book you will want to close again easily, unless for a moment of silence to contemplate the beauty of what you have just read before you return eagerly for more.

Zikr is the debut poetry collection of the writer and photographer Saaleha Idrees Bamjee. Once opened, it is not a book you will want to close again easily, unless for a moment of silence to contemplate the beauty of what you have just read before you return eagerly for more.

The Thames runs through it. North and south of the famous river lie the “hidden histories” of mostly forgotten women. London Undercurrents brings them vividly back into our literary consciousness in this remarkable collection, written and compiled by two of the city’s female poets. Joolz Sparkes and Hilaire researched the past of these two geographical spaces located around the natural aquatic divide and retrieved from its archives the voices of women who have occupied them throughout the ages: “Woke up to find / I’d lived here half my life. / Felt the pull of community. / Began to dig. Began to sow.”

The Thames runs through it. North and south of the famous river lie the “hidden histories” of mostly forgotten women. London Undercurrents brings them vividly back into our literary consciousness in this remarkable collection, written and compiled by two of the city’s female poets. Joolz Sparkes and Hilaire researched the past of these two geographical spaces located around the natural aquatic divide and retrieved from its archives the voices of women who have occupied them throughout the ages: “Woke up to find / I’d lived here half my life. / Felt the pull of community. / Began to dig. Began to sow.” Following her critically acclaimed debut memoir, Queen of the Free State, Jennifer Friedman returns with a sequel that takes us back to the moment when she was leaving the Free State for boarding school and continues her story into adulthood. The Messiah’s Dream Machine is spread over many more years and settings than the first book, and thus is perhaps more disjointed in its retelling of anecdotes from the chronicles of Friedman’s rather eccentric family. However, like its literary sibling, it focuses not only on a life full of adventure and discovery, but also on the darker sides of adolescence and of growing into the often unexpected roles fate has in store for us.

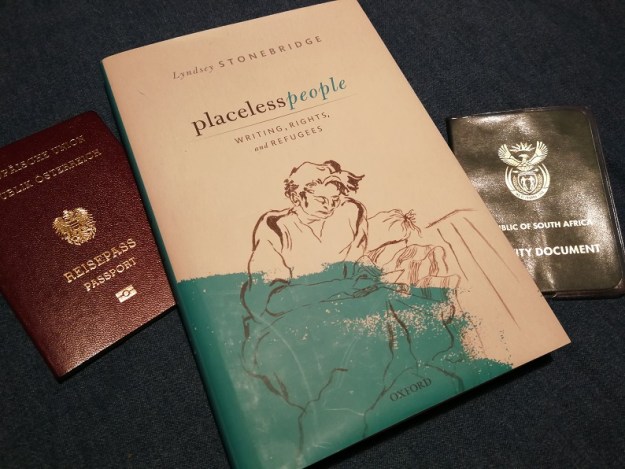

Following her critically acclaimed debut memoir, Queen of the Free State, Jennifer Friedman returns with a sequel that takes us back to the moment when she was leaving the Free State for boarding school and continues her story into adulthood. The Messiah’s Dream Machine is spread over many more years and settings than the first book, and thus is perhaps more disjointed in its retelling of anecdotes from the chronicles of Friedman’s rather eccentric family. However, like its literary sibling, it focuses not only on a life full of adventure and discovery, but also on the darker sides of adolescence and of growing into the often unexpected roles fate has in store for us. Throughout the ages, humans have been migrating across the globe; it is ingrained in our nature. Depending on time, place, and reason, these individual or mass movements of people have been welcomed or deplored by others. But being a refugee has never been easy. When you are forced to leave your home country and seek refuge elsewhere, whatever initiated the journey is usually only half of the ordeal you are facing – the uncertainty on the other side can be as daunting, if not more so.

Throughout the ages, humans have been migrating across the globe; it is ingrained in our nature. Depending on time, place, and reason, these individual or mass movements of people have been welcomed or deplored by others. But being a refugee has never been easy. When you are forced to leave your home country and seek refuge elsewhere, whatever initiated the journey is usually only half of the ordeal you are facing – the uncertainty on the other side can be as daunting, if not more so.

How to be a feminist? What does it mean to be a good parent, especially a good mother? What is success? What is justice and how does it relate to ethics? How can reading and writing help with the answers to these, and other, vital questions? Somewhere in Between is Niki Malherbe’s attempt at resolving some of these conundrums in the context of her own life. She dedicates her book “To all women who try hard to get the balance right and all the men who do too”.

How to be a feminist? What does it mean to be a good parent, especially a good mother? What is success? What is justice and how does it relate to ethics? How can reading and writing help with the answers to these, and other, vital questions? Somewhere in Between is Niki Malherbe’s attempt at resolving some of these conundrums in the context of her own life. She dedicates her book “To all women who try hard to get the balance right and all the men who do too”.