“Now, there are storytellers, and there are Storytellers”, the narrator of Water No Get Enemy, one of Fred Khumalo’s stories collected in Talk of the Town, tells us about Guz-Magesh, a larger than life character who features in two of the pieces: “His well of tales is bottomless.” He has that in common with his creator. Khumalo is the author of four novels. His short stories have been considered for prestigious awards and featured in several magazines and anthologies. Talk of the Town is his debut collection.

“Now, there are storytellers, and there are Storytellers”, the narrator of Water No Get Enemy, one of Fred Khumalo’s stories collected in Talk of the Town, tells us about Guz-Magesh, a larger than life character who features in two of the pieces: “His well of tales is bottomless.” He has that in common with his creator. Khumalo is the author of four novels. His short stories have been considered for prestigious awards and featured in several magazines and anthologies. Talk of the Town is his debut collection.

The titular story of the volume is told from the perspective of a child who witnesses how his enterprising and hard-working mother sets their family apart by not having the furniture she buys repossessed by creditors. When her luck changes, the mother relies on her unsuspecting children to protect her from the fate of most of their neighbours.

Khumalo’s range of settings and characters is versatile. He moves between the apartheid past to the present, and between several countries. Water Get No Enemy and The Invisibles are set in present-day Yeoville, but the former moves back in time to the Liberation Army camps in Angola.

The stories of This Bus Is Not Full! and Learning to Love take place in the US, where two South African men end up living, but not entirely fitting in. The longest story in the collection is set in neighbouring Zimbabwe and has the feel of an abandoned novel in the making.

Reading Khumalo’s stories, one’s imagination and sense of political correctness can be both challenged to their limits, and it is to his credit that he can make us curious and care about even the least likable characters. At the same time, his stories can be poignant and excruciatingly funny. That is what keeps one returning for more.

Talk of the Town

by Fred Khumalo

Kwela, 2019

Review first published in the Cape Times on 19 July 2019.

A seminal step in the right direction

A seminal step in the right direction

South African-born Louisa Treger used to work as a classical violinist before she turned to literature, first gaining a PhD in English at University College London and then trying her hand at creative writing. Her academic research focused on early 20th-century women writing and eventually resulted in her first novel, The Lodger, which told the story of Dorothy Richardson, a British author and journalist who was one of the earliest modernist novelists and, in her heyday, was considered among the greats of the era, but was subsequently neglected by readers and critics alike.

South African-born Louisa Treger used to work as a classical violinist before she turned to literature, first gaining a PhD in English at University College London and then trying her hand at creative writing. Her academic research focused on early 20th-century women writing and eventually resulted in her first novel, The Lodger, which told the story of Dorothy Richardson, a British author and journalist who was one of the earliest modernist novelists and, in her heyday, was considered among the greats of the era, but was subsequently neglected by readers and critics alike. The relationship between domestic workers and their employers in South Africa has a complex and deeply troubled history. Yet, it lies at the heart of many local homes, whichever side of this relationship you find yourself on: as job creator or taker. The connection between the two defines everyday life for millions of South Africans. For foreigners, it is often unfathomable. Thus, I found Ena Jansen’s study of the subject, Like Family: Domestic Workers in South African History and Literature, extremely illuminating.

The relationship between domestic workers and their employers in South Africa has a complex and deeply troubled history. Yet, it lies at the heart of many local homes, whichever side of this relationship you find yourself on: as job creator or taker. The connection between the two defines everyday life for millions of South Africans. For foreigners, it is often unfathomable. Thus, I found Ena Jansen’s study of the subject, Like Family: Domestic Workers in South African History and Literature, extremely illuminating. Zikr is the debut poetry collection of the writer and photographer Saaleha Idrees Bamjee. Once opened, it is not a book you will want to close again easily, unless for a moment of silence to contemplate the beauty of what you have just read before you return eagerly for more.

Zikr is the debut poetry collection of the writer and photographer Saaleha Idrees Bamjee. Once opened, it is not a book you will want to close again easily, unless for a moment of silence to contemplate the beauty of what you have just read before you return eagerly for more.

The Thames runs through it. North and south of the famous river lie the “hidden histories” of mostly forgotten women. London Undercurrents brings them vividly back into our literary consciousness in this remarkable collection, written and compiled by two of the city’s female poets. Joolz Sparkes and Hilaire researched the past of these two geographical spaces located around the natural aquatic divide and retrieved from its archives the voices of women who have occupied them throughout the ages: “Woke up to find / I’d lived here half my life. / Felt the pull of community. / Began to dig. Began to sow.”

The Thames runs through it. North and south of the famous river lie the “hidden histories” of mostly forgotten women. London Undercurrents brings them vividly back into our literary consciousness in this remarkable collection, written and compiled by two of the city’s female poets. Joolz Sparkes and Hilaire researched the past of these two geographical spaces located around the natural aquatic divide and retrieved from its archives the voices of women who have occupied them throughout the ages: “Woke up to find / I’d lived here half my life. / Felt the pull of community. / Began to dig. Began to sow.” Following her critically acclaimed debut memoir, Queen of the Free State, Jennifer Friedman returns with a sequel that takes us back to the moment when she was leaving the Free State for boarding school and continues her story into adulthood. The Messiah’s Dream Machine is spread over many more years and settings than the first book, and thus is perhaps more disjointed in its retelling of anecdotes from the chronicles of Friedman’s rather eccentric family. However, like its literary sibling, it focuses not only on a life full of adventure and discovery, but also on the darker sides of adolescence and of growing into the often unexpected roles fate has in store for us.

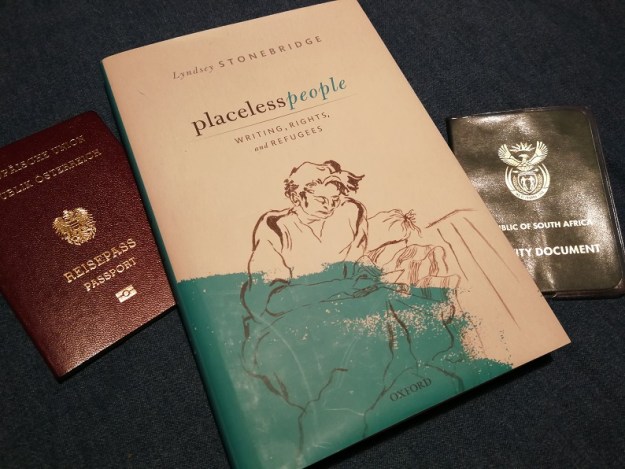

Following her critically acclaimed debut memoir, Queen of the Free State, Jennifer Friedman returns with a sequel that takes us back to the moment when she was leaving the Free State for boarding school and continues her story into adulthood. The Messiah’s Dream Machine is spread over many more years and settings than the first book, and thus is perhaps more disjointed in its retelling of anecdotes from the chronicles of Friedman’s rather eccentric family. However, like its literary sibling, it focuses not only on a life full of adventure and discovery, but also on the darker sides of adolescence and of growing into the often unexpected roles fate has in store for us. Throughout the ages, humans have been migrating across the globe; it is ingrained in our nature. Depending on time, place, and reason, these individual or mass movements of people have been welcomed or deplored by others. But being a refugee has never been easy. When you are forced to leave your home country and seek refuge elsewhere, whatever initiated the journey is usually only half of the ordeal you are facing – the uncertainty on the other side can be as daunting, if not more so.

Throughout the ages, humans have been migrating across the globe; it is ingrained in our nature. Depending on time, place, and reason, these individual or mass movements of people have been welcomed or deplored by others. But being a refugee has never been easy. When you are forced to leave your home country and seek refuge elsewhere, whatever initiated the journey is usually only half of the ordeal you are facing – the uncertainty on the other side can be as daunting, if not more so. Secret Keeper

Secret Keeper