Zikr is the debut poetry collection of the writer and photographer Saaleha Idrees Bamjee. Once opened, it is not a book you will want to close again easily, unless for a moment of silence to contemplate the beauty of what you have just read before you return eagerly for more.

Zikr is the debut poetry collection of the writer and photographer Saaleha Idrees Bamjee. Once opened, it is not a book you will want to close again easily, unless for a moment of silence to contemplate the beauty of what you have just read before you return eagerly for more.

In interviews, Bamjee talks about how the poems grew out of a deep sense of longing and loss, most poignantly expressed in poems like After a Miscarriage, or My World Today with the opening sentence “No babies yet”, or We Are Building Your House which ends with the lines “I have cleared a space in my mind, child / in my waking hours, and in my heart. / We are framing your memories, and waiting.”

Infertility, death, devotion and what it means to be an independent woman in a world of traditions are the major themes of this delicately woven volume. Its fabric is durable enough to hold the heaviest of struggles. One of my favourite pieces in Zikr is the prose poem Women on Beaches which includes the lines “The first bathing suit was a wooden house wheeled into the sea. They used to sew weights into hemlines. Drowning was a kind of modesty.”

The title of the book refers to “the remembrance of God” and some of the most powerful poems in the collection capture moments of exquisite spirituality: “My hands / are not big enough / to grasp prayer, / my tongue not loose enough / to utter them” (I, the Divine).

With Zikr, Bamjee establishes herself as a poet of grace, allowing readers to find solace and strength in her words: “I won’t pack sand around your heart. I will fill your mouth with zephyrs. / I will leave a bomb in your hand and quietly close the door.”

by Saaleha Idrees Bamjee

uHlanga, 2018

Review first published in the Cape Times on 14 June 2019.

Saaleha Idrees Bamjee with her publisher Nick Mulgrew at EB Cavendish

The Thames runs through it. North and south of the famous river lie the “hidden histories” of mostly forgotten women. London Undercurrents brings them vividly back into our literary consciousness in this remarkable collection, written and compiled by two of the city’s female poets. Joolz Sparkes and Hilaire researched the past of these two geographical spaces located around the natural aquatic divide and retrieved from its archives the voices of women who have occupied them throughout the ages: “Woke up to find / I’d lived here half my life. / Felt the pull of community. / Began to dig. Began to sow.”

The Thames runs through it. North and south of the famous river lie the “hidden histories” of mostly forgotten women. London Undercurrents brings them vividly back into our literary consciousness in this remarkable collection, written and compiled by two of the city’s female poets. Joolz Sparkes and Hilaire researched the past of these two geographical spaces located around the natural aquatic divide and retrieved from its archives the voices of women who have occupied them throughout the ages: “Woke up to find / I’d lived here half my life. / Felt the pull of community. / Began to dig. Began to sow.” Following her critically acclaimed debut memoir, Queen of the Free State, Jennifer Friedman returns with a sequel that takes us back to the moment when she was leaving the Free State for boarding school and continues her story into adulthood. The Messiah’s Dream Machine is spread over many more years and settings than the first book, and thus is perhaps more disjointed in its retelling of anecdotes from the chronicles of Friedman’s rather eccentric family. However, like its literary sibling, it focuses not only on a life full of adventure and discovery, but also on the darker sides of adolescence and of growing into the often unexpected roles fate has in store for us.

Following her critically acclaimed debut memoir, Queen of the Free State, Jennifer Friedman returns with a sequel that takes us back to the moment when she was leaving the Free State for boarding school and continues her story into adulthood. The Messiah’s Dream Machine is spread over many more years and settings than the first book, and thus is perhaps more disjointed in its retelling of anecdotes from the chronicles of Friedman’s rather eccentric family. However, like its literary sibling, it focuses not only on a life full of adventure and discovery, but also on the darker sides of adolescence and of growing into the often unexpected roles fate has in store for us. Throughout the ages, humans have been migrating across the globe; it is ingrained in our nature. Depending on time, place, and reason, these individual or mass movements of people have been welcomed or deplored by others. But being a refugee has never been easy. When you are forced to leave your home country and seek refuge elsewhere, whatever initiated the journey is usually only half of the ordeal you are facing – the uncertainty on the other side can be as daunting, if not more so.

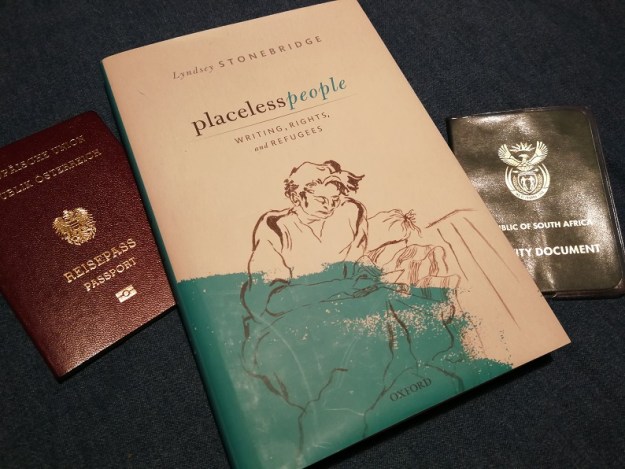

Throughout the ages, humans have been migrating across the globe; it is ingrained in our nature. Depending on time, place, and reason, these individual or mass movements of people have been welcomed or deplored by others. But being a refugee has never been easy. When you are forced to leave your home country and seek refuge elsewhere, whatever initiated the journey is usually only half of the ordeal you are facing – the uncertainty on the other side can be as daunting, if not more so. Secret Keeper

Secret Keeper

“Biography lovers may despair that the internet is making it improbable that biographers will still discover old, forgotten letters in dusty attics, revealing juicy secrets about celebrities. It still remains a problem when writers discard electronic records of their correspondence, but this book proves that emails can be every bit as romantic as old-fashioned letters, and all the more immediate.”

“Biography lovers may despair that the internet is making it improbable that biographers will still discover old, forgotten letters in dusty attics, revealing juicy secrets about celebrities. It still remains a problem when writers discard electronic records of their correspondence, but this book proves that emails can be every bit as romantic as old-fashioned letters, and all the more immediate.”