Pumla Dineo Gqola is a formidable writer who in her work discusses the most complex topics: slavery, stardom, rape, and feminism. She is the author of What is Slavery to Me? Postcolonial/Slave Memory in Post-apartheid South Africa, A Renegade Called Simphiwe, the 2016 Sunday Times Alan Paton Award winner Rape: A South African Nightmare, and the recently released Reflecting Rogue: Inside the Mind of a Feminist. A professor of African Literature at Wits University, Gqola has established herself as one of the leading intellectuals of the continent.

Reflecting Rogue comprises fourteen essays which range from academic to personal and often combine both approaches to tackle issues with socio-political implications and in the process gain a specific kind of authority because of their autobiographical touch: “I have revealed part of myself only known to my nearest and dearest: anxieties, joys, vulnerabilities.” As a way of introduction, Gqola recalls how as an eight-year-old she realised she was a writer when words offered her an escape into another language and thus freedom. She discovered the power of writing and writing’s relationship with power. It continues to be “at the centre of my life. It is where I love myself better.” She understands the risks involved, especially when you write from within the position of vulnerability that any intimate, personal writing entails. Unapologetically, she states: “There are reflections of and on living, loving and thinking as feminist. One feminist.”

The individual essays of the collection were written over a period of several years and offer insight into diverse subjects. In “Growing into my body”, Gqola traces the intricate relationship she has with her own “embodied memories”. Most readers will be able to relate to the perils implied: “I am not sure how much of myself I want to expose and render vulnerable, and so, instead, I play games with myself.” Racism, “notions of purity and contamination”, questions of approval and acceptance, are tough to consider and transcend. “It is crucial to begin to make new memories of embodiment”, Gqola writes, “forms that encourage pleasure and power.” She is heartened by seeing young Blackwomen “communicating comfort and love of themselves to themselves.”

“A Backwoman’s journey through three South African universities” is Gqola’s account of her experiences with “racist capitalist patriarchy” and her attempts to convert her “anti-racist and feminist politics into practice.” She advocates a thorough investigation of how “configurations of power mutate” and how we cope with the essential changes needed to avoid marginality of the majority of South African citizens. In another essay, Gqola quotes filmmaker Xoliswa Sithole who “argues repeatedly and convincingly about the manner in which Blackwomen are conned into embracing ‘modesty’ instead of owning our power, excellence and successes – and instead of openly celebrating each other’s.”

In two intensely introspective pieces on motherhood Gqola talks about how to be the best parent without compromising on a full life when the weight of entrenched women’s roles in partnerships and professional lives comes bearing down on your self-awareness and personal longings of fulfilment and independence. Gqola pays tribute to the people who helped her find a way “to belong to yourself and be committed to parenting well”.

She writes about the ideals and disappointments of freedom, of the “reminders of missed opportunities to create the country we dreamt of” and speaks about the dangers of ignoring differences when we negate the “need for accountability, atonement and justice” as well as not addressing the detrimental nature of heteropatriarchy. She argues for the necessity of “rage” in our dealing with the status quo, the speaking of truth to power instead of compliance and silence.

I had to dig deep into my academic past in order to follow Gqola’s discussion of the public’s conflicting responses to the exhibition Innovat1ve Women, curated by Bongi Bengu in 2009, but in general the book is incisive and accessible. Reflecting Rogue engages with underrepresentation of Black women in public spaces, whether political, creative or academic. Gqola recalls what it meant for her to encounter Alice Walker’s writing, how reading about black people’s lives in a black author’s work affirmed for her the possibility of becoming a writer. “A woman who does not want to apologise for valuing herself is a dangerous thing”, she states and gives reasons why she espouses womanism. Walker taught her “about letting go of the need for approval and external validation, which is so central to how women are raised all over the world.”

Discovering feminism was like a homecoming for Gqola, as it is for countless women independent of our backgrounds. We all believe in the same fundamental thing, but like any movement, feminism has developed different strands and allows for varied interpretations of which causes should take precedence and how they should be achieved. There were moments when I could relate to and at the same time felt alienated by passages in Reflecting Rogue. However, as Gqola claims, we are “rogues – unapologetically disrespectful of patriarchal law and order, determined to create a world in which choice is a concrete reality for all.” Part of that reality is Gqola’s choice to evoke Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, along with the Kenyan revolutionary Wambui Waiyaki Otieno and environmental political activist and Nobel Laureate Wangari Maathai, as women who “offer freeing visions of unsubjugated femininities.” I belong to the group of people Gqola mentions who can see little beyond Madikizela-Mandela’s involvement in “gross violations of human rights”, as stated in the final TRC report of 1998, and found her inclusion in the argument uncomfortably problematic.

Gqola’s tribute to the remarkable work of FEMRITE, the Uganda Women Writers Association, is free of such hauntings – a legacy entirely worthy of being celebrated. Reflecting Rogue also includes a public lecture Gqola gave during which she said: “Africa has to mean a present and a future home again for those who strive for a freedom linked to the freedom of those like – and unlike – us.” What I found most inspiring about Reflecting Rogue is the author’s unequivocal belief that “another world is possible.”

Reflecting Rogue: Inside the mind of a feminist

by Pumla Dineo Gqola

MF Books, 2017

An edited version of this review first appeared in the Cape Times on 20 October 2017.

Lara Feigel is a cultural historian and a literary critic, combining her interests to write about the meeting point between life, literature and history. In her last two books, she looks at how people whose quintessential purpose in life is the search for beauty and meaning survived their antithesis: war. In her The Love-charms of Bombs: Restless Lives in the Second World War (2013), Feigel wrote about five authors who were based in wartime London, driving ambulances, fighting fires, being creative, and loving passionately while desperately trying to remain alive.

Lara Feigel is a cultural historian and a literary critic, combining her interests to write about the meeting point between life, literature and history. In her last two books, she looks at how people whose quintessential purpose in life is the search for beauty and meaning survived their antithesis: war. In her The Love-charms of Bombs: Restless Lives in the Second World War (2013), Feigel wrote about five authors who were based in wartime London, driving ambulances, fighting fires, being creative, and loving passionately while desperately trying to remain alive. Dene Smuts once said that “there are two approaches to opposition lawmaking work: making a noise and making a difference.” Throughout her courageous life she chose to make a difference. Smuts completed the manuscript of Patriots and Parasites: South Africa and the Struggle to Evade History shortly before her unexpected death in April last year. Her daughter Julia midwifed the project to completion.

Dene Smuts once said that “there are two approaches to opposition lawmaking work: making a noise and making a difference.” Throughout her courageous life she chose to make a difference. Smuts completed the manuscript of Patriots and Parasites: South Africa and the Struggle to Evade History shortly before her unexpected death in April last year. Her daughter Julia midwifed the project to completion. There are times when people proclaim either the death of reading, or the death of the book as a physical object, or the death of bookshops, and no matter how much sceptics try to kill off one of the most engaging and enriching human experiences, it prevails and with it does the book and its private and public homes: bookshops and libraries. As any passionate reader will verify, bookshops can be oases of literary bliss. Jorge Carrión travelled around the world to visit many of them and wrote a fervent reminder of why they matter: “Every bookshop is a condensed version of the world.” South African readers will delight in the mention of local authors and favourites places such as the

There are times when people proclaim either the death of reading, or the death of the book as a physical object, or the death of bookshops, and no matter how much sceptics try to kill off one of the most engaging and enriching human experiences, it prevails and with it does the book and its private and public homes: bookshops and libraries. As any passionate reader will verify, bookshops can be oases of literary bliss. Jorge Carrión travelled around the world to visit many of them and wrote a fervent reminder of why they matter: “Every bookshop is a condensed version of the world.” South African readers will delight in the mention of local authors and favourites places such as the  “Who would want to read them?” we are asked at the back of Marike Beyers’s poetry collection, How to Open the Door. The answer is as easy as it is true: “Anyone interested in the recent inflection of various Englishes and … inflections of the ‘soul’.” In deceptively simple words Beyers captures complex memories of family scenes and relationship dynamics, stretching across time and space. There is loss, tenderness and pain: “here I am all razor blades / and concrete rubble / all corners sharp”. She is just as aware of language as of silence: “but there you stood / your mouth of broken birds”. There are people who live “outside of words”, but not the poet; “is it all too simple / is home then / this standing // in an open door”, she asks, and invites us to follow into the space of her poetic vision.

“Who would want to read them?” we are asked at the back of Marike Beyers’s poetry collection, How to Open the Door. The answer is as easy as it is true: “Anyone interested in the recent inflection of various Englishes and … inflections of the ‘soul’.” In deceptively simple words Beyers captures complex memories of family scenes and relationship dynamics, stretching across time and space. There is loss, tenderness and pain: “here I am all razor blades / and concrete rubble / all corners sharp”. She is just as aware of language as of silence: “but there you stood / your mouth of broken birds”. There are people who live “outside of words”, but not the poet; “is it all too simple / is home then / this standing // in an open door”, she asks, and invites us to follow into the space of her poetic vision. The image on the cover of Prunings, Helen Moffett’s second collection of poetry, is an exquisite unfinished painting of a broom karee branch. The poems in the slim chapbook are similarly delicate and unusually fragmented. Together with her editor and founder of uHlanga Press, Nick Mulgrew, Moffett decided to display the editorial process of pruning the individual pieces, but also entire poems which were cut from the volume and yet are still included in square brackets with horizontal lines struck through them. It is work in progress on show. The final effect of this innovative collaboration is one of wonder. What is supposedly excluded is as powerful as what remains:

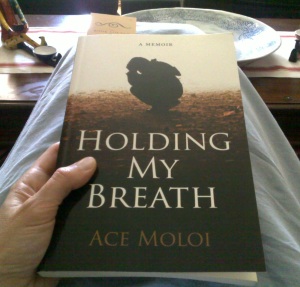

The image on the cover of Prunings, Helen Moffett’s second collection of poetry, is an exquisite unfinished painting of a broom karee branch. The poems in the slim chapbook are similarly delicate and unusually fragmented. Together with her editor and founder of uHlanga Press, Nick Mulgrew, Moffett decided to display the editorial process of pruning the individual pieces, but also entire poems which were cut from the volume and yet are still included in square brackets with horizontal lines struck through them. It is work in progress on show. The final effect of this innovative collaboration is one of wonder. What is supposedly excluded is as powerful as what remains:  Holding My Breath by Ace Moloi is a heart-wrenching, deeply inspirational grief memoir. Written in the form of a letter addressed to Moloi’s late mother, it tells his story before and after his mother’s death. He writes in the Prologue to the book: “I have decided to break the silence between us. I am starting this conversation to remind you of your younger son and to update you on my life.” Moloi points out that mourning is like learning a new language – “the language of living without you.” His mother died of an unexplained illness when he was thirteen and left him and his older brother to fend for themselves. Their father was absent when they were growing up. The boys had to rely on other family members for support. They encountered abandonment, hunger and despair as the divided family was mostly incapable of caring for them.

Holding My Breath by Ace Moloi is a heart-wrenching, deeply inspirational grief memoir. Written in the form of a letter addressed to Moloi’s late mother, it tells his story before and after his mother’s death. He writes in the Prologue to the book: “I have decided to break the silence between us. I am starting this conversation to remind you of your younger son and to update you on my life.” Moloi points out that mourning is like learning a new language – “the language of living without you.” His mother died of an unexplained illness when he was thirteen and left him and his older brother to fend for themselves. Their father was absent when they were growing up. The boys had to rely on other family members for support. They encountered abandonment, hunger and despair as the divided family was mostly incapable of caring for them. I was born in Poland, but as a student I used to live in Wales. About two years ago, I read a glowing review of Everything I Found on the Beach by the young Welsh writer Cynan Jones. The reviewer mentioned that the novel featured a Polish character. A Welsh novel with a Polish character was an irresistible combination for a reader with my literary background. I ordered and devoured it, and since then I have read every other novel or novella I could get hold of by the same author: The Long Dry, The Dig, and the latest, Cove.

I was born in Poland, but as a student I used to live in Wales. About two years ago, I read a glowing review of Everything I Found on the Beach by the young Welsh writer Cynan Jones. The reviewer mentioned that the novel featured a Polish character. A Welsh novel with a Polish character was an irresistible combination for a reader with my literary background. I ordered and devoured it, and since then I have read every other novel or novella I could get hold of by the same author: The Long Dry, The Dig, and the latest, Cove.

Founded and headed by author Sarah McGregor, Clockwork Books is a new independent local publisher with a growing list of fascinating titles. Its latest release is Pamela Power’s second novel, Things Unseen, a psychological thriller set in the posh suburbs of Johannesburg. I first read it in manuscript form, and remember that I had to pause and take a deep breath after the shocking violence of the opening scene in which we witness the terrifying demise of a person and an animal. Let’s just say that the rest of the book is also not for sissies.

Founded and headed by author Sarah McGregor, Clockwork Books is a new independent local publisher with a growing list of fascinating titles. Its latest release is Pamela Power’s second novel, Things Unseen, a psychological thriller set in the posh suburbs of Johannesburg. I first read it in manuscript form, and remember that I had to pause and take a deep breath after the shocking violence of the opening scene in which we witness the terrifying demise of a person and an animal. Let’s just say that the rest of the book is also not for sissies.