In the night of 9 February 2016, on the twelfth anniversary of my first arrival in Cape Town, I dreamt that I was in a hospital. In my dream, André died there. A few days later I came to pick up his belongings, but no one was willing to assist me. They shoved me around the place, ignoring my distress. I felt desperate, lost. I wanted to take care of his possessions but nobody was keen to help me. And then out of the blue someone offered support. I woke up, relieved.

I signed the contract for my memoir about the relationship I had with André, The Fifth Mrs Brink, that morning. Afterwards, I returned home to find that our grandfather clock had stopped working without any apparent reason. I got it going again, but both the dream and the silent clock disturbed me.

In the late afternoon, on my way to a book launch, I had a terrible car accident in which I killed our beloved Brink Mobil, the ancient green Mercedes André and I used to drive. My friends told me later that I did not kill the Old Lady, that she died protecting me. I couldn’t get rid of the feeling that having the accident on the same day I signed the contract was a sign, signalling some kind of closure or an impending massacre. I hoped for the former, but had no way of knowing which it would be.

Three weeks later, I walked across the city to pick up a rental car provided by my insurance company. Passing the accident spot on an overhead bridge, I could still see the rust-red stains where the Brink Mobil had bled to death.

I walked past the funeral parlour where they took André after his death – he did not die in a hospital but on board of an aeroplane flying over Brazzaville.

I also passed a big red building in Woodstock which caught my eye because it looked quite new and impressive. I considered getting a coffee from a place on its ground floor.

Woodstock is where long ago I once appeared on a friend’s doorstep in one of her dreams. She told me the next day that I’d looked lost and just stood there, clutching a book to my chest. The same friend works in the big red building now.

I finished the first draft of The Fifth Mrs Brink in July. In September, I asked for the rights to my book back. I had to leave; I had no way of staying. If I wanted to truly take care of my and André’s stories, I had to find a home for them elsewhere. I submitted my memoir to another publishing house. They made me an offer. My new publisher gave me a book she thought might interest me: Second-Hand Time by Svetlana Alexievich, an account of how people survive, and make sense of, tyranny and massacres – by weaving tapestries of stories to keep us safe at night. The words of Second-Hand Time live in my bones.

In the evening of the 1st of November, someone asked me online which great writer I would like to have tea with. There is only one: The One. He liked his tea white with two sugars. And when he wanted to spoil me, he baked scones for us for breakfast.

I don’t know what I dreamt in the night of the 1st of November, but I know I slept through it. That in itself is a gift, a good omen. Uninterrupted sleep had become rare in the past few months, although I am mastering it again. In the morning of the 2nd, I had a scone at my favourite coffee shop. I drove to Woodstock in the little car that a friend lent me after my accident. I parked underneath the big red building, found my way upstairs to the 4th floor where kind people were waiting.

It is perhaps fitting that the publication of The Fifth Mrs Brink will be delayed by a few months next year to coincide with the 30th anniversary of the first time I became a refugee when my family escaped the tyranny of Communist Poland and sought asylum in Austria.

Arriving on the doorstep of Jonathan Ball Publishers, I felt like a refugee who had sailed through treacherous waters in a derelict dinghy and found her way to the shores of a safe haven. With only my ancient fountain pen in the bag I carried, I was seeking asylum again.

Massacres and tyranny can be intimate, private, go nearly unnoticed.

I am not the only one who survives by telling stories.

My stories are safe now.*

*Sadly, they actually weren’t. Almost two years later, I know beyond a shadow of a doubt that as long as greed, and not integrity, governs people’s decisions, your stories will never be safe with them. But my stories will always be mine to tell and I intend to continue telling them, with integrity… (18 September 2018).

“This is what matters: to say ‘no’ in the face of the certitudes of power.” (André Brink)

“Perhaps all one can really hope for, all I am entitled to, is no more than this: to write it down. To report what I know. So that it will not be possible for any man ever to say again: I knew nothing about it.” (André Brink)

The overwhelming impression I had while reading Abner Nyamende’s There’s always tomorrow was that the novel had not been edited properly, if at all. It began with the first page, where the word “darkness” features six times without apparent reason. And the unnecessary repetitions are only the tip of the iceberg. After finishing, out of curiosity I looked up Partridge, the publishing house, and was informed that, although backed by a giant international trade publisher, the company provides only self-publishing services to their authors. Editing seems to be part of the professional packages on offer, but I cannot imagine that it was employed in this particular case. In this regard I was appalled at the quality of the final product, and it is a pity, because the book has an important story to tell. If the author did pay for editing of any kind, he was cheated…

The overwhelming impression I had while reading Abner Nyamende’s There’s always tomorrow was that the novel had not been edited properly, if at all. It began with the first page, where the word “darkness” features six times without apparent reason. And the unnecessary repetitions are only the tip of the iceberg. After finishing, out of curiosity I looked up Partridge, the publishing house, and was informed that, although backed by a giant international trade publisher, the company provides only self-publishing services to their authors. Editing seems to be part of the professional packages on offer, but I cannot imagine that it was employed in this particular case. In this regard I was appalled at the quality of the final product, and it is a pity, because the book has an important story to tell. If the author did pay for editing of any kind, he was cheated… Travelling in India, Karen Jennings visits an art gallery where “holograms of rare gold artefacts line the wall. A notice declares that precious items might be stolen and so holograms are the next best thing. They are fuzzy, unclear. It is like looking at an object at the bottom of a dirty pond.” It is a striking image that made me think of writing an autobiographical novel or a memoir. In the hands of a mediocre writer, recollections and artefacts can become like these blurred holograms. But Karen Jennings is not a mediocre writer.

Travelling in India, Karen Jennings visits an art gallery where “holograms of rare gold artefacts line the wall. A notice declares that precious items might be stolen and so holograms are the next best thing. They are fuzzy, unclear. It is like looking at an object at the bottom of a dirty pond.” It is a striking image that made me think of writing an autobiographical novel or a memoir. In the hands of a mediocre writer, recollections and artefacts can become like these blurred holograms. But Karen Jennings is not a mediocre writer.

The Bostik Book of Unbelievable Beasties

The Bostik Book of Unbelievable Beasties Cats

Cats

Reading a play is like listening to an opera on CD. Many would argue that both are best experienced on stage. There is nothing like a live performance, I agree. Yet, no matter how much I love going to the theatre or opera house, reading a play or listening to opera in the comfort of my own home can also be special.

Reading a play is like listening to an opera on CD. Many would argue that both are best experienced on stage. There is nothing like a live performance, I agree. Yet, no matter how much I love going to the theatre or opera house, reading a play or listening to opera in the comfort of my own home can also be special. Dream of the Dog was first written and appeared as a local radio play in 2006, and was rewritten and staged the following year in South Africa before transferring overseas. Its action takes place in KwaZulu-Natal. An aging couple sell their farm to developers. The man in charge of the project turns out to be the son of one of their former workers. As he returns to the place, he brings with him long-supressed memories of violence and death on the farm. The play inspired Higginson’s latest novel, The Dream House (2015), which won the prestigious

Dream of the Dog was first written and appeared as a local radio play in 2006, and was rewritten and staged the following year in South Africa before transferring overseas. Its action takes place in KwaZulu-Natal. An aging couple sell their farm to developers. The man in charge of the project turns out to be the son of one of their former workers. As he returns to the place, he brings with him long-supressed memories of violence and death on the farm. The play inspired Higginson’s latest novel, The Dream House (2015), which won the prestigious

In a corner, with no way out, when everything seems lost, broken, incomprehensible, a tiny light might save you. Holding on to that light is not an act of bravery. It is an act of compassion. I survive because I have kind people in my life. Perhaps recognising and reaching out for that kindness is courage? I do not know. I know that the sharing, the true care of friendship, have saved me from utter despair. The women in my life. I repeat: The women in my life. I do not know what I would have done without You. I salute and cherish you!

In a corner, with no way out, when everything seems lost, broken, incomprehensible, a tiny light might save you. Holding on to that light is not an act of bravery. It is an act of compassion. I survive because I have kind people in my life. Perhaps recognising and reaching out for that kindness is courage? I do not know. I know that the sharing, the true care of friendship, have saved me from utter despair. The women in my life. I repeat: The women in my life. I do not know what I would have done without You. I salute and cherish you! The first time I travelled to

The first time I travelled to

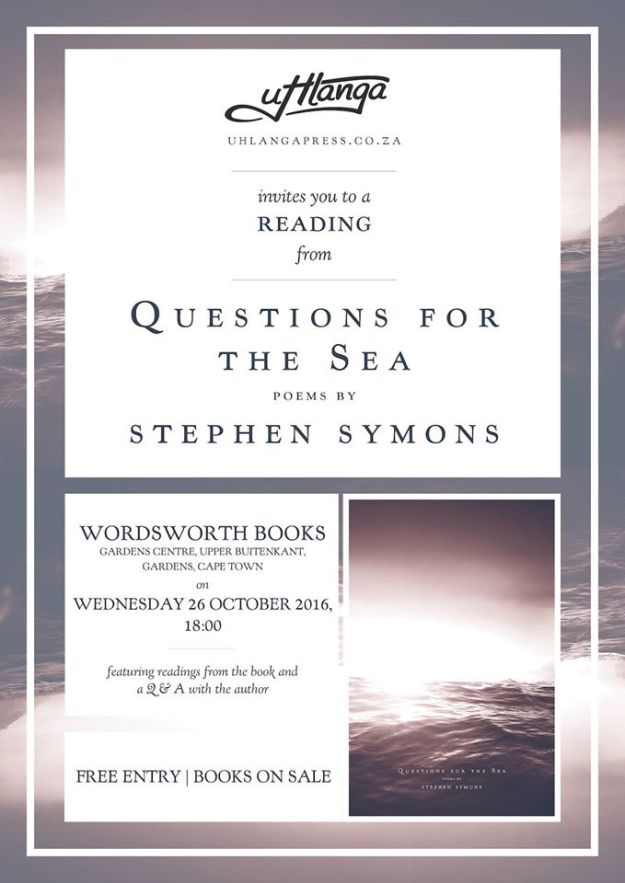

During the last McGregor Poetry Festival a poem was inscribed on the walls of Temenos, my favourite one from Stephen Symon’s stunning debut collection

During the last McGregor Poetry Festival a poem was inscribed on the walls of Temenos, my favourite one from Stephen Symon’s stunning debut collection  I arrived at Wordsworth Books rattled, but there were good friends, cheese and wine, and poetry – subtle, soul-restoring poetry. Beauty, like light, can save you. How precious that it can be contained in words. Thank you, Stephen and Nick, for caring about words.

I arrived at Wordsworth Books rattled, but there were good friends, cheese and wine, and poetry – subtle, soul-restoring poetry. Beauty, like light, can save you. How precious that it can be contained in words. Thank you, Stephen and Nick, for caring about words.

Questions for the Sea, the debut collection by Cape Town-based poet and graphic designer Stephen Symons is the latest exquisite offering from the independent local publisher, uHlanga. The sea, questions, light and poetry: an irresistible combination.

Questions for the Sea, the debut collection by Cape Town-based poet and graphic designer Stephen Symons is the latest exquisite offering from the independent local publisher, uHlanga. The sea, questions, light and poetry: an irresistible combination.

Camaraderie. That is the word which comes to mind when I think back to the one day I spent at the fabulous Soweto Theatre, attending the inaugural The Star Soweto Literary Festival. It was quite a whirlwind affair. A day of talks, improvisation, laughter and tears. I invited myself. The moment I heard that the festival was happening – and it was organised in a shockingly short amount of time – I volunteered to speak, chair sessions, whatever, just to be there. I felt it in my bones that it would be special, and I wanted to be part of it.

Camaraderie. That is the word which comes to mind when I think back to the one day I spent at the fabulous Soweto Theatre, attending the inaugural The Star Soweto Literary Festival. It was quite a whirlwind affair. A day of talks, improvisation, laughter and tears. I invited myself. The moment I heard that the festival was happening – and it was organised in a shockingly short amount of time – I volunteered to speak, chair sessions, whatever, just to be there. I felt it in my bones that it would be special, and I wanted to be part of it. The day I was there, Saturday, the presence of the spirits of these literary giants was palpable. The attempt to establish “a truly non-racial” space for writers, artists and the public to engage with one another’s ideas was a great success. I attended with a dear friend, Pamela Power, the author of Ms Conception and the upcoming psychological thriller, Things Unseen. We came away inspired, glowing, and moved to the core.

The day I was there, Saturday, the presence of the spirits of these literary giants was palpable. The attempt to establish “a truly non-racial” space for writers, artists and the public to engage with one another’s ideas was a great success. I attended with a dear friend, Pamela Power, the author of Ms Conception and the upcoming psychological thriller, Things Unseen. We came away inspired, glowing, and moved to the core.

For a white person, reading Writing What We Like: A New Generation Speaks might feel like gatecrashing a party where some ugly truths will be revealed about you. Provocative and penetrating, Writing What We Like is a difficult book to review when you happen to be white, because one feels that one should not be talking at all, but listening only. One is torn between possible accusations of one’s own “intellectual arrogance” and the need for dialogue. And yet, a way to disrupt entrenched ways of thinking and to establish connections across barriers imposed on us by a turbulent and harrowing history is to try to imagine ourselves into the skins of others. That is where creativity and empathy begin – in writing, reading and interpretation – where we cease to view ourselves in any other categories but human. The ultimate goal is understanding, coupled with compassion. Everything else will follow from there.

For a white person, reading Writing What We Like: A New Generation Speaks might feel like gatecrashing a party where some ugly truths will be revealed about you. Provocative and penetrating, Writing What We Like is a difficult book to review when you happen to be white, because one feels that one should not be talking at all, but listening only. One is torn between possible accusations of one’s own “intellectual arrogance” and the need for dialogue. And yet, a way to disrupt entrenched ways of thinking and to establish connections across barriers imposed on us by a turbulent and harrowing history is to try to imagine ourselves into the skins of others. That is where creativity and empathy begin – in writing, reading and interpretation – where we cease to view ourselves in any other categories but human. The ultimate goal is understanding, coupled with compassion. Everything else will follow from there.