It was an awkward situation. I was standing there, in front of my best friend’s door, with a cardboard box and an old suitcase in my arms, feeling foolish. I could hear her drying her hair inside. Taking a deep breath, I pressed the bell.

“Coming!” Marlene shouted, switching off the hairdryer.

When she opened the door, the dark hallway of the flat building was flooded with sunshine. It was the beginning of a hot summer day, the humidity in the air promising rain later in the afternoon. Marlene’s damp red curls looked on fire in the bright morning light.

She hovered in the doorframe, staring at the box and the suitcase, twisting one of her curls between a forefinger and a thumb.

“Hi,” I volunteered.

“Hi, come in.” She disentangled her fingers from her hair and swept her hand aside in a gesture of welcome. The flimsy bathrobe she was wearing came undone as she did so, and I glimpsed a perfect, small breast before she tied the garment tighter around her waist.

“This is weird,” she said, following me into the flat.

I pressed my lips together and agreed. “You can say that again.”

We were facing each other, not really knowing how to proceed. Nothing had prepared us for this odd situation.

“I don’t know.” She paused. “I don’t know whether all the clothes will fit into this suitcase.” She rushed through the second part of the statement. “The box might also be too small for all the other stuff,” she added with a shy smile.

“That’s alright, maybe you’ll have a bag or something for me?” I looked her straight in the eye, without returning the smile. I didn’t know what was really expected of me. Was I supposed to be distant? Angry? Sympathetic? I had no clue. Deep inside, I simply wanted to be neutral, but that didn’t feel right either. But how was I to pick sides?

“Right!” She gracefully turned on her bare heel. “Let me show you the stuff first.”

She led me to her bedroom. As always, the place was in a state of chaos. I never saw her make her bed, or pick up all the magazines and books from the floor. She was the fastest and least discriminating reader I knew; the likes of Dan Brown and Virginia Woolf were strewn all around us. We shared the passion of reading, but I was more careful with my choices, and I liked to be organised. Pedantic, is how Marlene described it. I preferred to think of myself as fastidious.

“That’s all I could find.” She pointed at a pile of clothes on the bed next to one of the crumpled pillows. “Some pieces were still in the laundry basket, so he might want to check.”

She reached for the box I was carrying. “Let me try to get the other stuff in here for you.”

While I was packing the suitcase, she put some DVDs, CDs, computer games and comic books from another pile on the floor into the box.

“I’ll get a plastic bag for the sneakers and the roller blades,” she said and left the room.

With difficulty I zipped up the bulging suitcase and looked at the box. I recognised the top CD cover: Lady Gaga. Kester once played the record for us. I tried to keep up with the latest in music, but some developments were beyond me.

Marlene returned, packed the remaining items, and handed me the bag.

“This won’t change anything between us, will it?” She was facing the window and the lucid sunlight illuminated her features again. I knew her well enough to recognise what was coming. I wasn’t good with tears, especially not hers.

“Of course not,” I reassured her, put the bag aside, and pulled her into a loose embrace. Her hair smelled like summer rain on hot concrete.

Continue reading: LitNet

The feeling one is left with after reading Sandra Hill’s debut story collection Unsettled is reflected in the title of the book. Hill paints vivid portraits of what it means to be a woman in different places and times. It is a finely layered picture of the everyday and the unusual. The mother of one of the characters insists that one should read poetry “slowly, expectantly, the way you eat oysters”, as the “magic…comes after you swallow.” Although every story is a fully contained piece, read together, they acquire that magic of swallowing oysters. Saturated with local flavours, settings, history, Unsettled offers evocative, intimate glimpses of women’s lives – their dreams, desires, worries and regrets – many readers will find uncannily familiar, sometimes perhaps difficult to acknowledge: “Life can take us away from where we belong, but we don’t lose the longing for it… If we are lucky we get to make our way back.”

The feeling one is left with after reading Sandra Hill’s debut story collection Unsettled is reflected in the title of the book. Hill paints vivid portraits of what it means to be a woman in different places and times. It is a finely layered picture of the everyday and the unusual. The mother of one of the characters insists that one should read poetry “slowly, expectantly, the way you eat oysters”, as the “magic…comes after you swallow.” Although every story is a fully contained piece, read together, they acquire that magic of swallowing oysters. Saturated with local flavours, settings, history, Unsettled offers evocative, intimate glimpses of women’s lives – their dreams, desires, worries and regrets – many readers will find uncannily familiar, sometimes perhaps difficult to acknowledge: “Life can take us away from where we belong, but we don’t lose the longing for it… If we are lucky we get to make our way back.” It’s difficult to believe that this is only

It’s difficult to believe that this is only  There is nothing quite as satisfying as an excellent personal essay, and William Dicey’s Mongrel contains six gems of the genre. Dicey has been on my literary radar for a while now. In the past decade, whenever I found myself admiring a beautifully designed local book, Dicey’s name would often feature on the copyright page. His first book, Borderline (2004), a travel memoir about canoeing on the Orange River, is one of those titles readers remember fondly whenever mentioned, but apparently, it is out of print. Fortunately, I found a copy in our library. I have been meaning to read it for years, and Mongrel has finally made me realise that I need to succumb to the longing.

There is nothing quite as satisfying as an excellent personal essay, and William Dicey’s Mongrel contains six gems of the genre. Dicey has been on my literary radar for a while now. In the past decade, whenever I found myself admiring a beautifully designed local book, Dicey’s name would often feature on the copyright page. His first book, Borderline (2004), a travel memoir about canoeing on the Orange River, is one of those titles readers remember fondly whenever mentioned, but apparently, it is out of print. Fortunately, I found a copy in our library. I have been meaning to read it for years, and Mongrel has finally made me realise that I need to succumb to the longing. Many of my friends will know

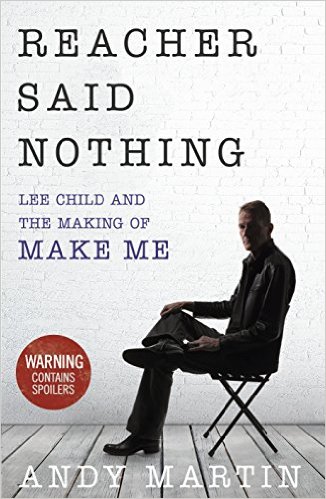

Many of my friends will know  Despite my irredeemable addiction to Lee Child’s Jack Reacher series, I do not often turn to thrillers or crime fiction for entertainment. But Night School, the next Reacher adventure, is coming out only in September, and since the nights are getting longer, it is nice to have a few good stand-ins in the meantime. Locally, I really enjoyed the recently published Sweet Paradise by Joanne Hichens: tight plotting, great writing, a scary villainess, and a heroine with balls. It surprised me, and that is a quality I truly appreciate in genre fiction.

Despite my irredeemable addiction to Lee Child’s Jack Reacher series, I do not often turn to thrillers or crime fiction for entertainment. But Night School, the next Reacher adventure, is coming out only in September, and since the nights are getting longer, it is nice to have a few good stand-ins in the meantime. Locally, I really enjoyed the recently published Sweet Paradise by Joanne Hichens: tight plotting, great writing, a scary villainess, and a heroine with balls. It surprised me, and that is a quality I truly appreciate in genre fiction. Reading about the Holocaust is never easy. Facing its terrible truths, especially when your own family is involved, is heroic.

Reading about the Holocaust is never easy. Facing its terrible truths, especially when your own family is involved, is heroic.

There are writers and then there are writers. Most of us can only dream of becoming the kind of writer Jacqui L’Ange already is, and the stunning The Seed Thief is only her debut novel. Her prose is luminous. It feels as if her words are caressing the pages they are printed on. Enthralled from the beginning, I was reading with bated breath, afraid that the author could not sustain such excellence through an entire novel, that she would take a false step, get lost along the way, and lose me as a reader. But The Seed Thief is one of those rare books which deliver on all fronts and leave you completely satisfied.

There are writers and then there are writers. Most of us can only dream of becoming the kind of writer Jacqui L’Ange already is, and the stunning The Seed Thief is only her debut novel. Her prose is luminous. It feels as if her words are caressing the pages they are printed on. Enthralled from the beginning, I was reading with bated breath, afraid that the author could not sustain such excellence through an entire novel, that she would take a false step, get lost along the way, and lose me as a reader. But The Seed Thief is one of those rare books which deliver on all fronts and leave you completely satisfied.

Every now and then, a book comes along which changes your life. For me, Roberto Calasso’s The Art of the Publisher is one of them. But you don’t have to be – or, like me, want to become – a book publisher to find this gem an inspiration.

Every now and then, a book comes along which changes your life. For me, Roberto Calasso’s The Art of the Publisher is one of them. But you don’t have to be – or, like me, want to become – a book publisher to find this gem an inspiration.