I have only done it once. On the Hurtigruten’s Trollfjord many, many years ago. It was spectacular – the fjords, the North Pole, the Northern Lights. A few hundred members of the Norwegian Book Club and many Norwegian and international writers were on board. A dream cruise for any literature lover.

I have only done it once. On the Hurtigruten’s Trollfjord many, many years ago. It was spectacular – the fjords, the North Pole, the Northern Lights. A few hundred members of the Norwegian Book Club and many Norwegian and international writers were on board. A dream cruise for any literature lover.

Since that bookish adventure on the Trollfjord, however, I have never really considered going on another ship cruise. After reading Sarah Lotz’s Day Four, I gave up on the idea altogether. For a while, I was intrigued by the possibility of travelling as a passenger on a cargo ship, but then I watched the silver screen version of Yann Martel’s Life of Pi and decided to abandon that idea, too. Yet, somewhere, somehow, a vague dream persisted of a week or two of uninterrupted plain sailing across the globe’s oceans, of sipping piña coladas next to a pool, of writing and reading the days away on deck, and of watching spectacular sunsets before retiring for a night of midnight blue solitude that a ship cabin with a view can offer.

And then, Cunard’s Queen Elizabeth II sailed into Cape Town’s arms and reawakened these subliminal longings. I had the opportunity to go on board with CapeTalk’s broadcasting team and was enchanted.

If you have never sailed on one of these ships before, it is difficult to imagine what to expect. During CapeTalk’s special outdoor broadcast, John Maytham interviewed Nikki van Biljon, the events manager of the luxurious ship, about her job and its joys and challenges. Listening, I remembered J.M. Coetzee’s descriptions of an author’s life on board of such a cruise in his Elizabeth Costello. A series of lectures or readings with captivated and appreciative passenger audiences would appeal to me as a writer, I think.

I was definitely thrilled to discover Susan Fletcher, one of my favourite authors, in the Library on board of Queen Elizabeth II. Her latest, House of Glass, is also already on my bookshelf and I look forward to reading it in the near future.

I recently read Graham Viney’s marvellous book, The Last Hurrah: The 1947 Royal Tour of Southern Africa and the End of Empire, and while boarding the ship named after one of the 1947 tour’s main royal guests, I recalled the evocative way Viney had described the approach of the ship that carried the royal family into Cape Town’s harbour in 1947.

I recently read Graham Viney’s marvellous book, The Last Hurrah: The 1947 Royal Tour of Southern Africa and the End of Empire, and while boarding the ship named after one of the 1947 tour’s main royal guests, I recalled the evocative way Viney had described the approach of the ship that carried the royal family into Cape Town’s harbour in 1947.

Viney also records Princess Elizabeth’s reaction on first seeing the Mother City: ‘It was a wonderful day as we approached Cape Town and when I caught my first glimpse of Table Mountain I could hardly believe that anything could be so beautiful.’

The ship named after now Queen Elizabeth impresses with its elegant interiors, an old-world charm that is irresistible to hopeless romantics like myself. You enter the main hall and cannot help thinking of similar scenes from the movie Titanic – the opulence and the beauty, the promise of an adventure (before the encounter with The Iceberg, of course). The live harp music started playing just after six pm, in time for dinner. Luckily, nobody was sinking. I did not count the restaurants and bars on board, but there seemed to be many, something for every taste.

The ship named after now Queen Elizabeth impresses with its elegant interiors, an old-world charm that is irresistible to hopeless romantics like myself. You enter the main hall and cannot help thinking of similar scenes from the movie Titanic – the opulence and the beauty, the promise of an adventure (before the encounter with The Iceberg, of course). The live harp music started playing just after six pm, in time for dinner. Luckily, nobody was sinking. I did not count the restaurants and bars on board, but there seemed to be many, something for every taste.

I painted my nails pale blue, wore my dark blue princess dress and perfume, and felt unusually glamorous.

A selfie with the Queen seemed compulsory. She celebrated her twenty-first birthday during that famous tour of 1947. In a few days, I will be twice her age of the time. The average on board of the QEII is probably thrice as much or even more, so maybe a sea voyage like this should wait for a while yet. But ever since visiting the ship, I have been fantasising about sailing for two or three weeks, a stranger among strangers, and writing, writing, writing. With no everyday distractions, and only the sea as my companion, I could probably have a rough draft of a novel at the end of such an expedition. The mere possibility is incredibly tempting…

A selfie with the Queen seemed compulsory. She celebrated her twenty-first birthday during that famous tour of 1947. In a few days, I will be twice her age of the time. The average on board of the QEII is probably thrice as much or even more, so maybe a sea voyage like this should wait for a while yet. But ever since visiting the ship, I have been fantasising about sailing for two or three weeks, a stranger among strangers, and writing, writing, writing. With no everyday distractions, and only the sea as my companion, I could probably have a rough draft of a novel at the end of such an expedition. The mere possibility is incredibly tempting…

So while I dream on, here is my review (first published in the Sunday Times on 23 December 2018) of Graham Viney’s book:

The monarchy is not my cup of tea, thus I was rather surprised how thoroughly Graham Viney’s The Last Hurrah had charmed me. Talking about the book to other readers, it has also been intriguing to discover how firmly this particular historical moment is lodged in the psyche of the country, no matter where you or your family stood on the broad spectrum of local politics of the era. Viney’s portrayal of the complex time before the infamous elections of 1948, and the role the royal visit played in it, brings the bygone days with all their vibrant possibilities and uncertainties to life. There is a strong sense that it all could have turned out differently. It is a dizzying thought which should not be underestimated, especially at present, when South Africa is once again transitioning before a potentially monumental election and so much could be at stake.

Viney writes with flair. His is a strikingly literary tour of the British royal family’s grand visit to South Africa as he puts his readers in the front seat, or rather in the main carriages, of the White Train that transported the distinguished guests over vast distances around the country from February to April 1947. Viney asks us “to conjure up the pervading smells of heat and dust, of acrid railway-engine smoke and cinders, of eucalyptus and pepper trees, of Yardley’s Lavender and the friendly tang of the Indian Ocean on a summer’s morning”, among a list of other sensations that his evocative descriptions capture for us to enjoy. They allow a total immersion into the past, akin to time travel.

“I could hardly believe that anything could be so beautiful”, wrote Princess Elizabeth after her first sighting of Table Mountain. Up close, we witness the royals arriving in Cape Town by ship, trekking across this part of the continent as far as Victoria Falls and Durban, and stopping along the way wherever people gathered to welcome them. It was a spectacle like no other. “‘We have to be seen to be believed’ is an oft-repeated adage of the Royal Family,” as Viney reminds us. Anyone who’d followed the most recent royal wedding in Britain might understand how everywhere the royal family appeared at the time (long before television and the internet), people of all races and creeds flocked to see them. The visit provided rare opportunities “in the context of the segregated society” when all people could still come together to participate in some of the events scheduled.

Viney records the triumphs and tribulations of the journey, including the King’s Opening of Parliament and, “to the astonishment of everyone”, his few lines in Afrikaans; the slight caused by the royal itinerary which allocated only two days of their time to Johannesburg; the Ngoma Nkosi at Eshowe; the tea the royal family had with Mrs Smuts and other guests who were secretly in attendance; as well as “the climax of the tour” – Princess Elizabeth’s 21st birthday celebrations and her moving speech which was broadcast worldwide to around 200 million people.

The book is richly illustrated and includes never before published photographs. Viney’s meticulous research and fluent prose result in a full-bodied portrait of the royal tour, its charged politics and all the major players involved, each with his or her own agenda. However, his narration is never bogged down by unnecessary details as he sweeps us along on this remarkable trip, when “for one brief shining moment much of South Africa had put their best foot forward and pulled together.”

Lara Feigel is a cultural historian and a literary critic, combining her interests to write about the meeting point between life, literature and history. In her last two books, she looks at how people whose quintessential purpose in life is the search for beauty and meaning survived their antithesis: war. In her The Love-charms of Bombs: Restless Lives in the Second World War (2013), Feigel wrote about five authors who were based in wartime London, driving ambulances, fighting fires, being creative, and loving passionately while desperately trying to remain alive.

Lara Feigel is a cultural historian and a literary critic, combining her interests to write about the meeting point between life, literature and history. In her last two books, she looks at how people whose quintessential purpose in life is the search for beauty and meaning survived their antithesis: war. In her The Love-charms of Bombs: Restless Lives in the Second World War (2013), Feigel wrote about five authors who were based in wartime London, driving ambulances, fighting fires, being creative, and loving passionately while desperately trying to remain alive. Dene Smuts once said that “there are two approaches to opposition lawmaking work: making a noise and making a difference.” Throughout her courageous life she chose to make a difference. Smuts completed the manuscript of Patriots and Parasites: South Africa and the Struggle to Evade History shortly before her unexpected death in April last year. Her daughter Julia midwifed the project to completion.

Dene Smuts once said that “there are two approaches to opposition lawmaking work: making a noise and making a difference.” Throughout her courageous life she chose to make a difference. Smuts completed the manuscript of Patriots and Parasites: South Africa and the Struggle to Evade History shortly before her unexpected death in April last year. Her daughter Julia midwifed the project to completion. There are times when people proclaim either the death of reading, or the death of the book as a physical object, or the death of bookshops, and no matter how much sceptics try to kill off one of the most engaging and enriching human experiences, it prevails and with it does the book and its private and public homes: bookshops and libraries. As any passionate reader will verify, bookshops can be oases of literary bliss. Jorge Carrión travelled around the world to visit many of them and wrote a fervent reminder of why they matter: “Every bookshop is a condensed version of the world.” South African readers will delight in the mention of local authors and favourites places such as the

There are times when people proclaim either the death of reading, or the death of the book as a physical object, or the death of bookshops, and no matter how much sceptics try to kill off one of the most engaging and enriching human experiences, it prevails and with it does the book and its private and public homes: bookshops and libraries. As any passionate reader will verify, bookshops can be oases of literary bliss. Jorge Carrión travelled around the world to visit many of them and wrote a fervent reminder of why they matter: “Every bookshop is a condensed version of the world.” South African readers will delight in the mention of local authors and favourites places such as the  “Who would want to read them?” we are asked at the back of Marike Beyers’s poetry collection, How to Open the Door. The answer is as easy as it is true: “Anyone interested in the recent inflection of various Englishes and … inflections of the ‘soul’.” In deceptively simple words Beyers captures complex memories of family scenes and relationship dynamics, stretching across time and space. There is loss, tenderness and pain: “here I am all razor blades / and concrete rubble / all corners sharp”. She is just as aware of language as of silence: “but there you stood / your mouth of broken birds”. There are people who live “outside of words”, but not the poet; “is it all too simple / is home then / this standing // in an open door”, she asks, and invites us to follow into the space of her poetic vision.

“Who would want to read them?” we are asked at the back of Marike Beyers’s poetry collection, How to Open the Door. The answer is as easy as it is true: “Anyone interested in the recent inflection of various Englishes and … inflections of the ‘soul’.” In deceptively simple words Beyers captures complex memories of family scenes and relationship dynamics, stretching across time and space. There is loss, tenderness and pain: “here I am all razor blades / and concrete rubble / all corners sharp”. She is just as aware of language as of silence: “but there you stood / your mouth of broken birds”. There are people who live “outside of words”, but not the poet; “is it all too simple / is home then / this standing // in an open door”, she asks, and invites us to follow into the space of her poetic vision. The image on the cover of Prunings, Helen Moffett’s second collection of poetry, is an exquisite unfinished painting of a broom karee branch. The poems in the slim chapbook are similarly delicate and unusually fragmented. Together with her editor and founder of uHlanga Press, Nick Mulgrew, Moffett decided to display the editorial process of pruning the individual pieces, but also entire poems which were cut from the volume and yet are still included in square brackets with horizontal lines struck through them. It is work in progress on show. The final effect of this innovative collaboration is one of wonder. What is supposedly excluded is as powerful as what remains:

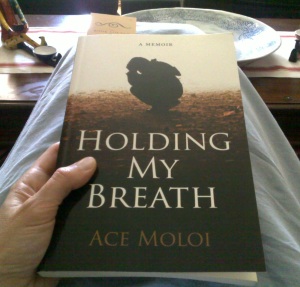

The image on the cover of Prunings, Helen Moffett’s second collection of poetry, is an exquisite unfinished painting of a broom karee branch. The poems in the slim chapbook are similarly delicate and unusually fragmented. Together with her editor and founder of uHlanga Press, Nick Mulgrew, Moffett decided to display the editorial process of pruning the individual pieces, but also entire poems which were cut from the volume and yet are still included in square brackets with horizontal lines struck through them. It is work in progress on show. The final effect of this innovative collaboration is one of wonder. What is supposedly excluded is as powerful as what remains:  Holding My Breath by Ace Moloi is a heart-wrenching, deeply inspirational grief memoir. Written in the form of a letter addressed to Moloi’s late mother, it tells his story before and after his mother’s death. He writes in the Prologue to the book: “I have decided to break the silence between us. I am starting this conversation to remind you of your younger son and to update you on my life.” Moloi points out that mourning is like learning a new language – “the language of living without you.” His mother died of an unexplained illness when he was thirteen and left him and his older brother to fend for themselves. Their father was absent when they were growing up. The boys had to rely on other family members for support. They encountered abandonment, hunger and despair as the divided family was mostly incapable of caring for them.

Holding My Breath by Ace Moloi is a heart-wrenching, deeply inspirational grief memoir. Written in the form of a letter addressed to Moloi’s late mother, it tells his story before and after his mother’s death. He writes in the Prologue to the book: “I have decided to break the silence between us. I am starting this conversation to remind you of your younger son and to update you on my life.” Moloi points out that mourning is like learning a new language – “the language of living without you.” His mother died of an unexplained illness when he was thirteen and left him and his older brother to fend for themselves. Their father was absent when they were growing up. The boys had to rely on other family members for support. They encountered abandonment, hunger and despair as the divided family was mostly incapable of caring for them.