Unexpectedly, it felt like a homecoming. Our Dragonair flight from Hong Kong to Beijing landed in the late afternoon. From the moment we left the arrivals hall something in the air made me want to curl up inside myself and simply return to where we came from. And it was not the chilling wind; nor the constant drizzle.

The grey architecture’s sharp and unimaginative lines, the bleak atmosphere, the poverty and hopelessness of masses, the condescending attitudes of people in any kind of authoritative position, the schemers operating below the radar of the system, and the uncanny impression of being constantly watched as if surrounded by an omnipotent, unpredictably scary, presence – almost instantly I was transported back to the time I was growing up in Eastern Europe still under the thumb of communist rule, before the political changeover of the late 1980s. Something engrained in my bones, but dormant for so many years, resurfaced in recognition.

The traffic policeman in charge of the taxi flow at the Beijing Capital International Airport shoved us aside and signalled for us to wait. It transpired that we were judged to have too much luggage to fit into an ordinary taxi, with no other kind of taxi in sight. There were three of us, each in possession of a suitcase and a piece of hand luggage. We tried to suggest that we could at least attempt to load the luggage into a car or separate and take two taxis, but both ideas were rejected. After a while of hopeless waiting, a rickety minibus arrived, clearly not an official taxi. The driver ‘generously’ offered to take us all to our hotel for about twice the usual fee. We did not have a choice but to accept.

An insignificant scene, one could say, but it was just the beginning. For the reminder of the trip I was constantly aware of this familiarity between the Poland of my childhood and the present-day China and I marvelled again at the destructive power of the ideology behind the resemblance, at how two countries of such diverse cultural backgrounds – Eastern European and Asian – could be reduced to eerie similarity under the pressures of a single system of thought.

But beside the ache in my bones, the experience of discovering a few spots of China was one of the most memorable ones of my entire travelling life. For the first time, I realised what Americans were doing when they ‘did’ Europe in two weeks. Our attempt was of a similar nature. My husband André Brink and I visited China to attend two literary festivals, in Hong Kong and Shanghai. The invitation was facilitated by a dear friend of André’s, Gary Kitching, who kindly offered to accompany us not only to the official literary events but on most of our journey through the Land of the Dragon. Apart from visiting the two festival cities, we used the opportunity to fulfil lifelong dreams of walking on the Great Wall and seeing the warriors of Emperor Qin Shi Huang’s Terracotta Army.

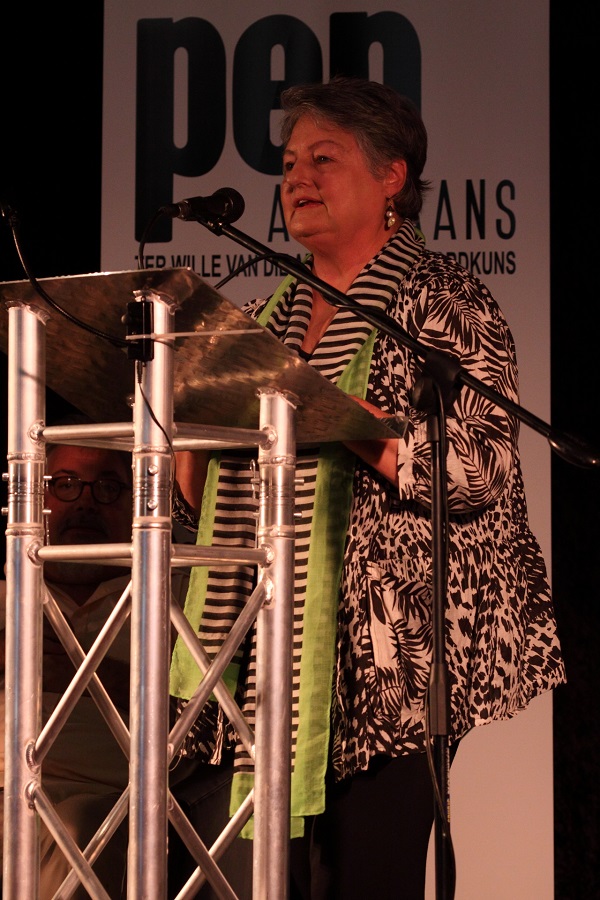

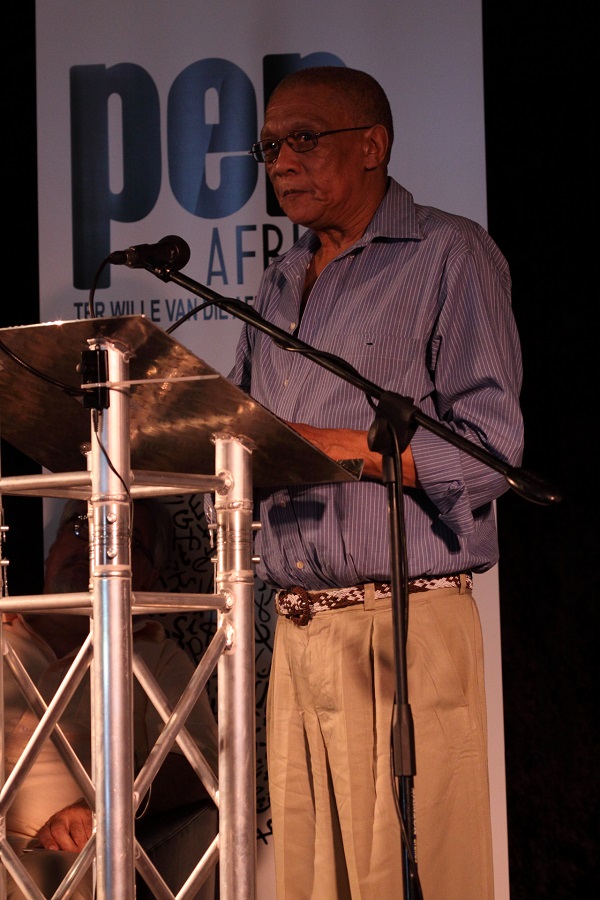

It was our honour and pleasure to share parts of the journey with another South African writer, Mandla Langa who, like André, was a guest of both literary festivals. Mandla Langa’s latest novel, The Lost Colours of the Chameleon (2008) won the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for Africa Region in 2009. During the two festivals Mandla read from the novel and spoke very movingly about his work, the hardships of exile, and the tragedy of having to cope with his brother’s death at the hands of the ANC. At shared events, Mandla and André discussed the different sides of the literary and political struggle they were both involved in during apartheid. On a more positive note, they shared with their enthusiastic audiences their feelings of optimism about the explosion of creativity in the New South Africa.

In Hong Kong at one of the literary events, together with Mandla, André was interviewed by Rachel Holmes, author of The Secret of Dr James Barry (2002) and The Hottentot Venus: The Life and Times of Saartjie Baartman (2007). She reminded them of the occasion they had met in London when Mandla was still in exile. André described the encounter in his memoir, A Fork in the Road (2008). He went to see Mandla and Essop Pahad at the time. As he took his leave, André was offered a packet of ANC coffee from Kenya and was told that they would drink it together when they were all allowed to come home “one of these days”. “The coffee will still be fresh,” André was reassured. Mandla accompanied him to the tube. André recalls in the memoir: “I walked huddled over the small packet I was carrying like precious loot under my arm. Mandla walked inclined towards me as if he, too, wanted to claim possession. Perhaps we were both imagining the flavour of that coffee: the smell of tomorrow. One of these days.”

For both of them, and for myself, the time of tasting freedom has arrived when at last we all found ourselves living in democratic countries, post-1994 South Africa and Austria respectively. But while we were travelling in China, signs of the ongoing repression and fear were everywhere: the Rio Tinto trial began in Shanghai amongst secrecy and doubt in the fairness of the process, Google was finally on its way out of the country refusing to accept the censorship imposed on the search engine, and an interview with the outspoken Chinese artist and activist Ai Weiwei, a victim of censorship and state violence, was repeatedly shown on BBC World. Very tellingly, there were hardly any Chinese readers attending the festival events.

Even before arrival in the country, while applying for our visas we were told not to mention the fact that we were writers, academics or had any associations with the media. This might have either endangered the positive outcome of the application or at least made the process much more tedious, we were warned. So, André travelled as a retired teacher, I as a housewife. Neither was a direct lie, but both statements were far removed from the truth. The application went smoothly. To our great surprise, the Chinese Consulate in Cape Town even distributed free DVDs about the Dalai Lama. We did not dare take one when applying for the visa, suspicious of the unexpected offer (a possible test of the worthiness of the applicant?), but could not resist bringing it back home once the visas had been granted. We were curious whether it was a piece of propaganda. But it turned out to be shrewder than that. We only managed to watch thirty minutes of what seemed a factually correct documentary. Then we fell asleep; it was so boring. Clever, we thought.

We also discovered that in spite of being widely publicised in the print and online media, the literary festival in Shanghai we attended was strictly speaking illegal. This kind of schism is also part of the system I remembered from growing up. You constantly live your life on the border of legality. Your actions are tolerated until you overstep a line. Where that line is precisely located you never know until you cross it, and then all which has been ignored till then will be counted against you.

As a special administrative region, reflecting the policy known as “one country, two systems”, Hong Kong still enjoys a high degree of autonomy in all areas except defence and foreign affairs. The city hosted its literary events officially. Celebrating their tenth anniversary with a bang, the festival organisers invited the likes of Alexander McCall Smith, Junot Díaz, Louis de Bernièrs, Linda Jaivin, and Mo Zhi Hong whose debut novel The Year of the Shanghai Shark (2008) won the Best First Book for South East Asia and Pacific of the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize 2009 (the same year as Mandla won with The Lost Colours of the Chameleon).

The Hong Kong and Shanghai festivals often collaborate in bringing authors to the their audiences. So some faces were more or less familiar when we arrived in Shanghai. Contrary to expectations, literary festivals or conferences seldom offer good opportunities of getting to know other writers, especially if one is rather shy by nature, which, maybe surprisingly, many writers are. In spite of many organiser’s efforts to put them into social situations, writers often end up lonely in hotel rooms, passing the time from one event to another with TV or mini-bar content (more often than not, both), or if the gatherings take place in interesting settings, desperately trying to see as much of the area as possible. The latter happened to us, when André and I spent every free minute exploring Hong Kong and Shanghai instead of listening to other guests of the festival, no matter how alluring.

We did however, even if only briefly, catch up with Linda Javin, Louis de Bernièrs, and Mo Zhi Hong in Shanghai. On the terrace of the fabulous “M on the Bund” Restaurant (venue and one of the main sponsors of the festival), over James Bond martinis and the exotic Dragon’s Pearl cocktails we listened to the wonderfully flamboyant Linda Javin, author of the best-selling A Most Immoral Woman (2009), talking about her latest project, a traditional Chinese opera based on a story from a Ming Dynasty novel for which she has been asked to write the libretto. We actually managed to attend Louis de Bernièrs’s official event during which he delighted the audience with a reading of “Obadiah Oak, Mrs Griffiths and the Carol Singers”, a story from his recent collection Notwithstanding (2009), and charmed us all with his infectious sense of humour. With Mo Zhi Hong we shared a taxi to the airport in Shanghai and after a brief conversation were very sorry not to have been able to spent more time in the company of this erudite young man. The festival over, he was on his way back home to Auckland and we were travelling to Xi’an for our appointment with the world-famous Terracotta Army.

One of Emperor Qin Shi Huang’s megalomaniac ventures, the terracotta warriors are a sight to behold. What struck me most about visiting China’s well-known places of interest was that in spite of seeing them numerous times on television programmes or in photography books, one is not prepared for their size. Constantly I had to readjust the images in my head to the real thing. The Great Wall of China (also Emperor Qin Shi Huang’s brainchild) does not impress with its height, as I expected. It is actually quite low and narrow for most of its unfathomable length. But when you stand on one of its vantage points and it stretches away from you in both directions over the mountain ranges like a ribbon carelessly discarded on the seemingly impenetrable landscape, it takes your breath away. In Beijing, the infamous Tiananmen Square is so vast that one can hardly see from one side of it to the other and walking across it in bitter cold was quite a challenge. The Forbidden City is actually a city within the capital. We began our tour of it at the northern entrance and it took us over four hours of almost continuous walking to reach the South Gate where Chairman Mao’s portrait overlooks the scene of the terrible massacre which took place in 1989.

Similarly, no matter how often one had seen them on television, the enormous excavation pits near the city of Xi’an where the Terracotta Army stands exposed after thousands of years of existing only in legends, are simply awe-inspiring. Each individually crafted and meticulously reassembled after centuries of being buried in mud, the warriors testify to the outrageous and murderous dreams of a single individual. Thousands of craftsmen and workers were tortured and killed during the execution of Qin Shi Huang’s vision of the army that was to protect him in the afterlife. Since their discovery just over thirty years ago, thousands of archaeologists, scientists and helpers have been meticulously putting the warriors’ remains together to make them, and what they stand for, known to the world. I walked around the pits and was terrified by the hunger for power and greatness which called this army into being. It was a chilling experience, but I admired the incredible reconstruction work on site and the amount of knowledge experts have gathered about ourselves and our past from the excavation pits. If only we would learn from it.

Other ‘visionaries’ ruled the land. After the so-called Cultural Revolution of the late 1960s when China’s innumerable treasures were destroyed and a whole generation of artists annihilated, the country is in the throes of another ‘cultural revolution’, this time brought about by Big Money and Big Mac. Like many other fast-growing economies, China is in constant flux, its authenticity challenged by the same forces which are at work in South Africa and other westernised parts of the world. Recently modernised for the Olympic Games, China still looks like one gigantic building site. Entire cityscapes are dominated by high-rise flat buildings which function as dormitories for the expanding population. Transport networks, shopping malls, factories, office buildings, and all kinds of institutions rise from the ground like mushrooms after the rain. The one constant is forests of cranes. Higher, bigger and faster seems to be the motto for everything. I can imagine that architects must have a field day in a country where their imaginations are required to go beyond all limits.

One of the most spectacular modern sites we saw was the architecturally mind-boggling Pudong skyline in Shanghai, the characteristic Oriental Pearl Tower dominating the scene. Over the last two decades the district has become home to China’s commercial and financial buzz. Just across the Huangpu river from Pudong is Shanghai’s best-known historical landmark, the Bund. While we were visiting, we witnessed the exciting preparations for the World Expo all along its beautiful promenade.

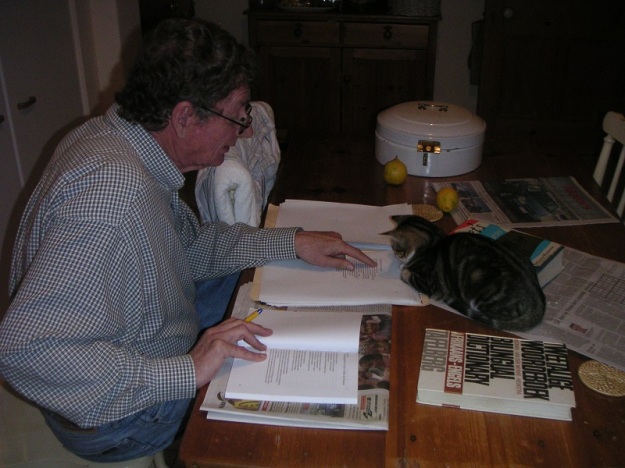

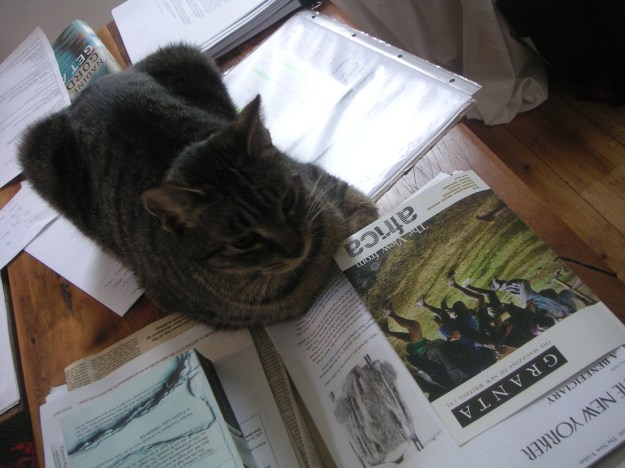

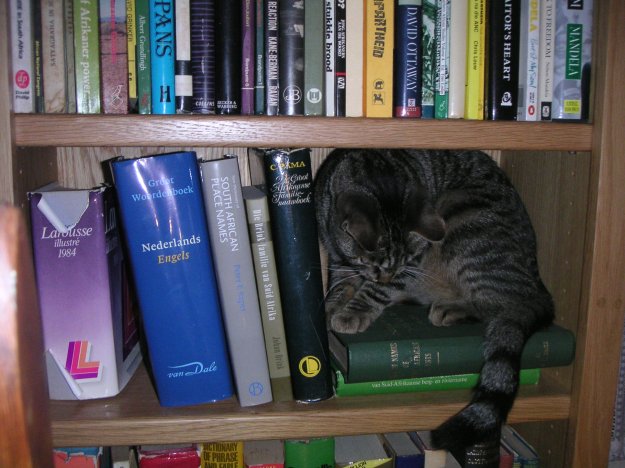

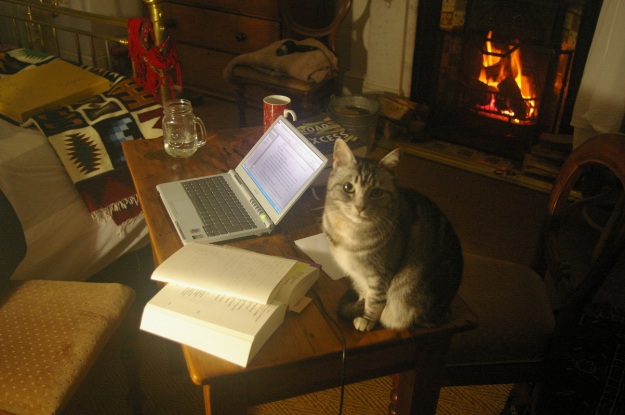

Yet, among all the splendour and chaos, the one place in China that is truly lodged in my memory is the Old China Hand Reading Room, a small antique book-cum-tea shop located in one of the quieter streets of the French Concession, another of Shanghai’s historical districts. It was founded by photographer Deke Erh and writer Tess Johnston and strikes the perfect balance between past and present, between Chinese and Western influences. Furnished with antique furniture and stocked with hundreds of old and new publications as well as many quirky trinkets of local and international origins, the shop is a must for all tea and book lovers. They also serve excellent cappuccinos in ancient porcelain cups. Just the thing after a long Sunday morning walk through the Concession, as André and I discovered.

Everywhere else we had what one really should have while travelling through China: tea. It is served at every opportunity, its distinct flavours and the rituals to bring them forth cultivated through millennia-old traditions. I have always loved tea but never appreciated it as much as after the visit to China. The souvenir I cherish most from our visit is my collection of exquisitely embroidered, colourful silk pouches from the Laoshe Teashop in Beijing which was recommended to us by our dear friend Alex Smith, the author of the travel memoir Drinking from the Dragon’s Well (2008). Inside the pouches conceal such wonders as Dancing Fairies, Love at First Sight, Birds of Heaven, and Whispering Flowers. If you put them in a transparent teapot and pour mild boiling water over them, the little green tealeaf bundles which are known by these fantastic names open up like blossoms and release a string of flowers – jasmine or lily – from their centre. The taste is as marvellous as the spectacle.

It is good to be back in Cape Town, where I’m truly at home, and to enjoy a bit of Chinese magic. Not all can be lost for a people who can create such perfect little artworks in a teacup. They may yet survive the dreams and visions of ‘Great Men’. And in spite of everything that is going wrong in our own country, I gain strength from the unsurpassed surge of creativity we are experiencing at the moment in South Africa. I just hope that my bones won’t begin to ache here, and I wonder whether I will ever be granted a Chinese visa again. Or will this article be placed in a file with my name on it, hidden away in some obscure cabinet?

First published in WORDSETC 8 (August 2010).